Mindfulness refers to both a practice and a state of mind. The more you practice it, the more it becomes your state of mind. Mindfulness is about generating greater mental effectiveness, so you can realize more of your potential on both a professional and a personal level. Effectiveness in this context is the ability to achieve your goals, objectives, and wishes in life.

Mindfulness training tools and techniques have been around for thousands of years. In our work with organizations around the world, we keep the practice and definition of mindfulness simple and close to its ancient roots: paying attention, in the present moment, with a calm, focused, and clear mind.

At the center of the practice of mindfulness is learning to manage your attention. When you learn how to manage your attention, you learn how to manage your thoughts. You learn to hold your focus on what you choose, whether it’s this page, an e-mail, a meeting, or the people you are with. In other words, you train yourself to be more present in the here and now.

Recently, research has backed up the claims that practitioners have been making for years. Mindfulness has a positive impact on our physiology, psychology, and work performance. At the physiological level, researchers have demonstrated that mindfulness training results in a stronger immune system, lower blood pressure, and a lower heart rate. In addition, people who practice mindfulness sleep better and feel less stressed.

Mindfulness training increases the density of grey cells in our cerebral cortex, the part of the brain that thinks rationally and solves problems. Because of this increase, cognitive function improves, resulting in better memory, increased concentration, reduced cognitive rigidity, and faster reaction times. With all these benefits, research has found people who practice mindfulness techniques report an overall increased quality of life.

The benefits of mindfulness also have been demonstrated in an organizational context. For example, Jochen Reb, a researcher from Singapore Management University, evaluated the effectiveness of some of our mindful leadership programs at Carlsberg Group and If P&C Insurance, a large Scandinavian insurance company. He found significant improvements in focus, awareness, memory, job performance, and overall job satisfaction after only nine weeks of training for 10 minutes each day. Attendees also reported reduced stress and improved perceptions of work-life balance. Other researchers have found similar benefits from mindfulness training in corporate contexts, including increased creativity and innovation, improved employer-employee relations, reduced absenteeism, and improved ethical decision making.

But mindfulness does something far more powerful than all of the above—it constructively alters our perception of reality. Through repeated practice, mindfulness triggers a shift in cognitive control to frontal brain regions. This enables us to perceive our world, our emotions, and other people without fight- or- flight and knee-jerk reactions and to have better emotional resilience.

This change in neurological wiring helps us perceive situations and make decisions more from the conscious mind, avoiding some of the traps of our unconscious biases. Operating more from the prefrontal cortex also enhances our executive function, the control center for our thoughts, words, and actions. A well- developed executive function allows us to better lead ourselves and others toward shared goals. With stronger prefrontal activity, we deactivate our tendency to be distracted and we become more present, focused, and attentive. Not coincidentally, mindfulness also makes us happier. The more present and attentive we are, regardless of what we do, the happier we become.

There are two key qualities of mindfulness—focus and awareness. Focus is the ability to concentrate on a task at hand for an extended period of time with ease. Awareness is the ability to make wise choices about where to focus your attention. Optimal effectiveness is achieved when you’re simultaneously focused and aware.

Focus and awareness are complementary. Focus enables more stable awareness, and awareness enables focus to return to what we’re doing. They work in tandem. The more focused we become, the more we also will be aware—and the other way around. In mindfulness practice, you enhance focus and awareness together.

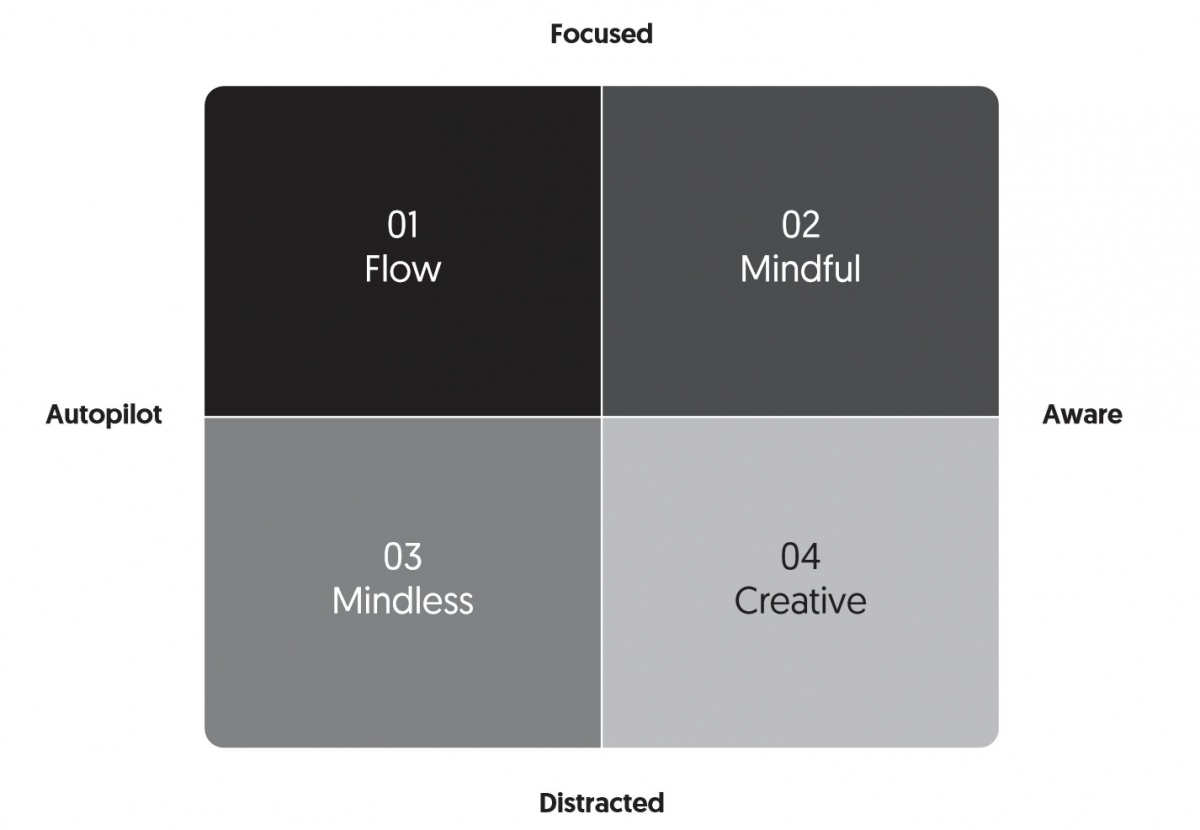

Mindfulness can be presented in a two- by- two matrix, as shown in the graphic below.

In the lower left quadrant, you’re neither focused nor aware. There is really not much good to say about this state of mind. Most of the mistakes we make arise from this mind state. And in leadership, as elsewhere, this can be harmful. If we are distracted and on autopilot, we are not present with our people. We can’t expect team members to be engaged and feel supported if we ourselves are not fully present.

In the lower right quadrant, you’re aware but easily distracted. Great ideas may arise from this state. But if your mind is too distracted, you’ll have difficulty retaining them and turning them into actions. Good ideas only become innovative solutions when you have the focus to retain and execute them by bringing them into the upper right quadrant.

Looking at the upper left quadrant, when you’re focused but on autopilot, your state of mind can be described as being in “flow.” It can be useful for routine tasks or when exercising. But the problem with this state is that we are not very aware and, therefore, are at risk of missing out on valuable information. Without awareness, we may not notice the expressions of the people we are meeting with, and hence we may exercise poor judgment. Also, without awareness, we are not able to see or understand our unconscious biases and may make bad decisions.

In the upper right quadrant—“mindful”—we are focused and aware. We are focused on the people we are with and the tasks we do. And at the same time, we have self- awareness and the ability to see our unconscious bias and regulate accordingly. In today’s always-on and distracted office environments, these two key qualities help us be mentally agile and effective.

In mindfulness practice, we train both our focus and our awareness. When we’re mindful, we’re able to overcome our mind’s natural tendency to wander. We can maintain focus on an object of our choice, notice when we get distracted, and then make decisions about where to place our attention. When we’re mindful, we also have a greater awareness of what we’re experiencing internally and externally. We can observe our thoughts as they arise and make best judgments about what to focus on and what to let go.

Over the years, we, along with our colleagues, have been teaching and training on mindfulness to leaders and employees in hundreds of organizations all over the world. Our approach has been developed and refined in collaboration with researchers, mindfulness experts, and business leaders. This practice is fundamental to your success in mastering mindful leadership.

Once you begin applying mindfulness to your leadership, you’ll see that as your mindfulness increases, your perception of “self” starts to change. More specifically, a stronger sense of selfless confidence arises, helping you develop the second quality of MSC leadership.

Excerpt from “The Mind of the Leader: How to Lead Yourself, Your People, and Your Organization for Extraordinary Results.” Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review Press. Copyright 2018 Rasmus Hougaard and Jacqueline Carter. All rights reserved.

Rasmus Hougaard is the founder and managing director of Potential Project, a global leader in customized leadership and organizational training programs based on mindfulness. With a proven track record of enhancing individual and collective performance, resilience, and creativity, Potential Project works with Fortune 500 companies such as Accenture, Microsoft, Lego, Nike, EY, and KPMG across North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Hougaard has led more than 1,500 workshops and programs and is recognized as a leading international authority on training the mind to be more focused, effective, and clear in an organizational context. Hougaard is a regular contributor to publications such as Business Insider and Harvard Business Review for his thought leadership and knowledge. He was selected for the 2018 Thinkers50 Radar list of 30 up-and-coming management thinkers most likely to shape how organizations are managed and led in the years ahead.

Jacqueline Carter is an international partner and the North American director for Potential Project. She has more than 20 years of experience working with organizations around the globe to enhance effectiveness and improve performance. Her clients include: Cisco, Accenture, Marriott, Google, RBC, and KPMG, to name a few. Carter has spoken at numerous conferences and has appeared on television and radio talk shows. She is a regular contributor to business publications, including Harvard Business Review, and is a sought-after speaker for her thought leadership, knowledge, and engaging facilitation skills. She holds a Master’s degree in organizational behavior and undergraduate degrees in labor management relations and mathematics. Before joining Potential Project, Carter held a number of senior leadership roles. She also worked for Deloitte in the U.S., Canada, and Australia in its Change Leadership practice.