Everyone makes decisions. Some decisions are big; others are small. Some are made on the spot. Others require time and more thought. This process of thinking and deciding goes on throughout the day.

Decision-making lies at the center of life. So much revolves around decisions people make—career choices, how plans are made, the way tasks are performed, and the formation of relationships. Yet, despite its centrality, people go about this central activity of deciding in vastly different ways. Some go fast; others go slow. Some stick to a particular plan; others modify plans readily. How one goes about this process has very important consequences.

The “How” of Decision-Making

If decisions are made too swiftly, important facts can be overlooked, and mistakes are made. If decisions are made too slowly, opportunities can slip away. If one sticks too tenaciously to a course of action, decisions reached could be irrelevant, inappropriate, or damaging. If one changes direction too often, team players, colleagues, or others can be thrown off course and resources squandered.

The reality is that there is no one best way to make a decision. There are many variables, including the kind of decision, the context, and the changing nature of the conditions; how unusual and complicated the situation and issues are; and how much time pressure there is. This simple idea—no one best way—makes sense, but because of powerful habits of thinking and deciding, it often goes unnoticed in the moment.

These habits become “decision styles.” Everyone has his or her own style. Although people shift their styles from time to time, there usually is one or two a person will gravitate toward more often than other styles. Ideally, individuals would adopt a style appropriate for the situation at hand—a quick style when time is of the essence; a thoughtful style when the situation is complex and important consequences are at stake; a fluid style when things are changing. But habits are powerful, and this doesn’t always happen.

Diversity and Agility

In working with leaders and teams, it is clear that teams with a diversity of styles among members outperform more style-homogeneous teams. The diversity means the team has the ability to deal with a variety of situations. Someone on the team will be equipped with the right style for any situation that arises.

Style diversity gives the team agility. More than ever, agility is required to survive and succeed. Enterprises are facing more complex and turbulent environments. Demand for innovations is on the rise. Products and services are undergoing constant revision. Things change quickly, almost without warning. Sudden disruptions render existing business models obsolete. Organizations and the teams within them must be agile to thrive in this environment.

Four Essential Decision Styles

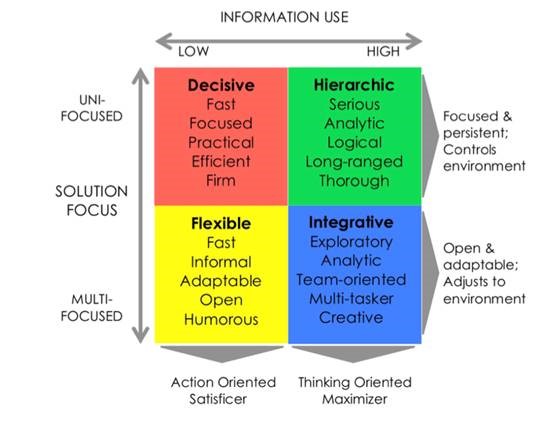

Here is a model of styles of thinking and deciding that clearly describes four essentials that teams need.

The styles shown in the table differ in two ways. On the horizontal axis, the styles differ in terms of amount of information considered when making decisions. The two styles on the left use just a few key facts. They are action-oriented and are called “satisficer” styles. The two styles on the right are “maximizer” styles—a maximum of information is taken in before a decision is reached.

On the vertical axis, the styles on the top row are “uni-focused.” They look for a path to achieve a very specific goal. When such a path is identified, they stick with it and don’t swerve. The two styles on the bottom are “multi-focused.” They target multiple objectives, not just one. Because no one path will achieve multiple goals, decisions made are multi-pronged and require a variety of paths. Further, those paths might change as the situation itself evolves. They are more variable in behavior than the uni-focused styles.

Decision Styles and Best Fit Situations

The key to using this framework is to know each style’s potential strong points and weak points and the type of decision situations that each style fits. Here’s a quick overview.

In teams, a skilled team facilitator or an experienced leader can use descriptions like the ones above or assessments designed to measure these behaviors to accomplish multiple goals. They can help team members understand different styles, recognize them in themselves and in teammates, and use them to great advantage to navigate decisions large and small that they inevitably will face. Individuals see their own “sweet spots” where they can and should unleash their styles. They also learn to recognize those situations where it’s better to toss the ball to someone else and to whom in particular that should be. They develop tolerance for styles other than their own and learn how to develop the agility that is so important in today’s complex and turbulent environments. Armed with these new insights, a team’s energies and capabilities are freed up to adroitly handle most any challenge that will come its way.

Kenneth R. Brousseau, Ph.D., is CEO of Decision Dynamics, a firm that specializes in the development and application of behavioral assessment tools that can be used for executive recruitment, executive coaching, team development, and career advisement. Before founding Decision Dynamics, Brousseau was an assistant professor of Management – Organizational Behavior at the University of Southern California. He earned his Ph.D. from Yale University. For more information, call 805.660.3950 or e-mail kenb@decdynamics.com.