A perennial hot topic in our field is how to align training with business strategy and needs. A recent Google search for “aligning Learning & Development (L&D) with business strategy” yielded nearly 31 million hits. Clearly, many people in our field think this is important.

Corporations are making significant financial investments in training—total U.S. training expenditures in 2015/2016 were $70.6 billion, according to Training magazine’s latest Training Industry Report. Those investments need to help achieve an organization’s strategy, and enhance individual and organizational performance in meaningful ways.

When training aligns with the business, employees at all levels understand expectations, operationalize vision and values, and recognize what is necessary to succeed. Conceptually, it is not hard to truly align training with the business needs, but it requires a good deal of work.

PERSPECTIVE: REFINING THE PROCESS

My first exposure to this issue occurred in 1985 when I was with consulting firm Xerox Learning Systems (now MHI Global). It provided a course for all client-facing staff on linking business needs with learning solutions. In the mid-1980s, that was cutting edge. But since that time, the approach has been explored in depth, and the methodology has become increasingly refined and sophisticated. Now the field agrees that training should align with business strategy, and there are established methodologies to do so.

One example of a well-structured approach was developed in 2002 when I was at Pfizer, which was ranked No. 1 on Training magazine’s Training Top 125. John Albright, a director of Leadership Development, created a strategy with supporting tactics that focused on maximizing learning transfer and sustainability. Key to the success of the approach was the linkage of learning to business performance. It turns out that if people have a clear line of sight from what they learn to how it can improve their performance—and a clear understanding of how their performance impacts the organization’s performance—they learn better and transfer that learning back to the job. There are a number of other factors that have an impact, such as support from their direct manager, availability of resources, etc. But when there is strong and explicit alignment with business strategy and needs, these other factors often fall into place.

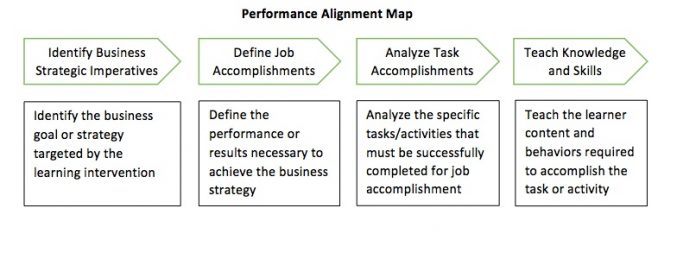

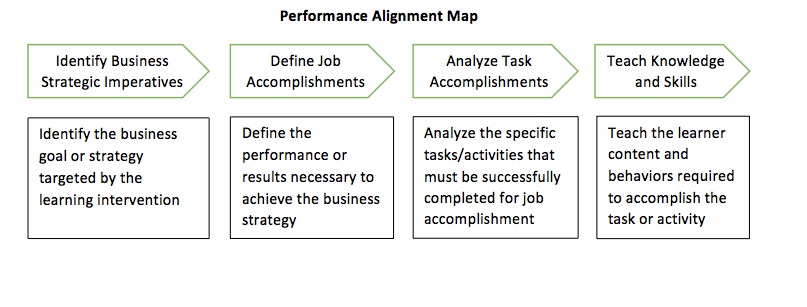

The Performance Alignment Map below is an example of a well-established methodology to link what is important for the business with what is important for the learner.

WHY SHOULD TRAINING PAY ATTENTION TO BUSINESS STRATEGY?

Simon Sinek’s TED talk, “How Great Leaders Inspire Action,” suggests that you start by answering the question, “why,” before proceeding to the “how” and “what.” Roy Pollock, one of the authors of “The Six Disciplines of Breakthrough Learning,” agrees with that approach and specifies that Training professionals need to define the “why” as the achievement of critical business outcomes the organization needs to accomplish.

Similarly David Ulrich recommends an “HR Outside In” approach. At a recent SHRM conference, he advocated for understanding the organizational context composed of “social, technological, economic, political, environmental, and demographic considerations.” He also noted that the context needs to be combined with an understanding of “inside” stakeholders such as employees and line managers, as well as “outside” stakeholders such as customers, investors, and communities. These then define the business issues the organization faces. HR and Training need to be able to talk the language of the business and demonstrate that they can help the organization be successful.

A 2015 article in Sloan Management Review, “Aligning Corporate Learning with Strategy,” by Shlomo Ben-Hur, Bernard Jaworski, and David Gray, follows a similar prescription for action in order to resolve their core point: “Too many corporate learning and development programs focus on the wrong things. A better approach to developing a company’s leadership and talent pipeline involves designing learning programs that link to the organization’s strategic priorities.”

WE CAN SOLVE THIS

We know we must tie training to organizational strategy and business needs. Why can’t we figure out how to do it?

I think our dilemma is a result of the “Knowing vs. Doing” gap. Most of the profession intellectually knows what to do—the problem is turning an intellectual understanding into action.

How does the L&D professional close the Knowing vs. Doing gap and gain buy-in for the learning agenda?

Try this three-pronged integrated approach:

The first step takes advantage of existing structures and processes. Have effective governance mechanisms linking the business to the Learning function been put into place? Governance provides an efficient formal and sanctioned pathway for building partnership, responsiveness, and allocation of resources. When I was at GE, there was a series of meetings tied to running the business that provided an “operating rhythm,” pulling the HR and line functions together and giving them common goals. This approach is driven home by a 2015 McKinsey study, which found that linking learning to business performance is critical, and happens best when HR and the business co-own learning.

The second step requires selling and consulting skills. When I was an L&D director, team leader at Pfizer, we looked at our meetings with line managers as “sales calls” rather than “meetings.” An effective sales call required the L&D team to identify the issues important to that manager and decide what we might be able to do to resolve the need. Before the sales call, we practiced how to articulate our value proposition in ways that would make sense to that particular line leader. We also prepared “proof sources,” and identified senior stakeholders to support our point of view and help us achieve our objective for the sales call. Perhaps most important, we created a list of questions to help structure the discussion and explore the topic. This last point is critical, because almost all of us are action oriented. As L&D consultant Bob Pike emphasized in a recent Training magazine article, asking questions provides critical information if you are to add value and make a difference to your organization and clients.

The third step is to become a trusted advisor. Performance consultant Dana Gaines Robinson talks about the ACT Model: Access, Credibility, and Trust.

- Access means having “face time” with the line leader. You may make an appointment, work on a committee, or follow a range of activities that will give you access and exposure.

- Credibility is built on results. This is where being able to link learning to results is critical. Using business language and linking learning to key performance indicators demonstrates a knowledge of the business and how it works—which builds credibility.

- Trust is based on maintaining confidences and holding oneself accountable. In addition, ensuring that your deeds match your words will create a feeling of personal authenticity that helps to facilitate the role of trusted advisor.

A CALL TO ACTION FOR L&D PROFESSIONALS

The intellectual understanding is not enough. You know how to diagnose business issues, map these issues to learning outcomes, create the training design, and then measure the outcomes. Here’s what you have to add: good relationships and communication with line leadership. Understanding how to create relationships with senior leaders and demonstrate the business case for learning will increase learning’s impact and make learning indispensable to the organization’s success.

Ross Tartell, Ph.D., is currently adjunct associate professor of Psychology and Education at Columbia University. Dr. Tartell also consults in the areas of learning and development, talent planning, and organization development. He received his M.B.A. in Management and his Ph.D. in Social Psychology from Columbia University. He formerly served as Technical Training and Communications Manager – North America at GE Capital Real Estate.