“Since employees have job descriptions, they should know what’s expected in their positions.”

I still remember the day I was hired into CareSource, a managed Medicaid plan in the Midwest United States. It was an exciting time for me. The six-hour interview worked out, and I was the top candidate. I also recall meeting with my new boss on my first workday. She was a VP and she spent an hour sharing her expectations with me. It was a good meeting, and I was anxious to show she had made the correct hiring decision. Now, fast-forward seven years and I have advanced from an adult education facilitator to a leadership development and performance management position. In the leadership programs I facilitate, I tell the audience, “I cannot remember one word from the expectations conversation with my boss seven years ago. I know we had the conversation, but if you told me my life depended on recalling those expectations, well, I would not be here today.”

Have You Ever Been Disappointed With Results?

A mistake we make in leadership and in training (more about the training environment a little later) is to believe we do well in establishing our expectations. Whether expectations are for a task or a class, we believe we have prepared staff and participants for success. And there lies the challenge: “We believe,” but did we really give the correct and enough information? We believe the conversations we had two, five, or seven years ago are fully retained by our employees. And we don’t understand why an employee isn’t following those expectations. Additionally, when we establish expectations, we rarely share what level of autonomy and responsibility we are giving our employees. This leads to misunderstanding, missed deliverables, or surprises when the completed work is revealed. Either the employee fell short or far exceeded the expectation—and may have moved too far with the goal or project. But did we clearly establish the expectation, level of autonomy, and responsibility in the beginning?

How Much Responsibility and Empowerment Do You Give Your Employees?

Susan Scott, in her book, “Fierce Conversations” (Scott, S. (2002). “Fierce Conversations: Achieving Success at Work & in Life, One Conversation at a Time.” Viking Press, New York, NY), speaks about having conversations in the context of decisions, actions, and reporting. Scott relates there are four levels to these conversations, and those levels reveal the amount of autonomy and responsibility an employee is given. With that clarity, all employees would know the level of empowerment they have been given to complete their responsibilities. They would understand whether they are allowed to make decisions or perform interoffice coordination, and whether they are required to report back to the boss. Imagine having conversations with your employees and, up front, you are clear about your expectations. Will you or they make and act on the decision? Should the employees consult with you before making and acting on decisions and are there any consultation or reporting requirements? If you do this, you will have covered all the bases and employees will have no doubt about what is allowed in meeting responsibilities. I am sure you can envision the results if all our conversations were like that.

The Common Failure When Facilitating

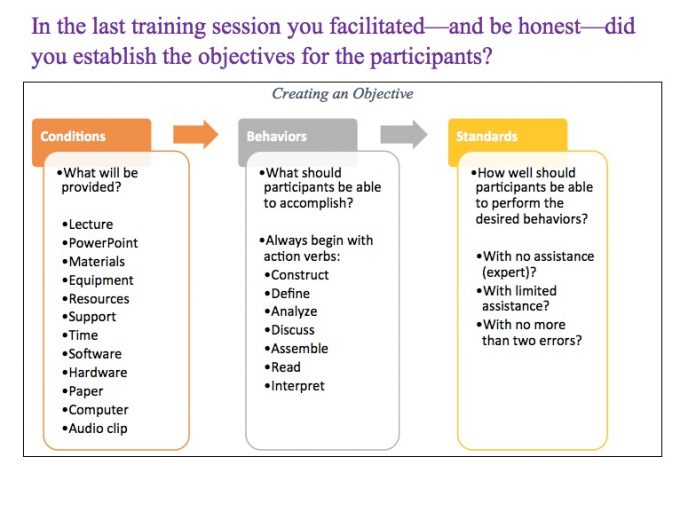

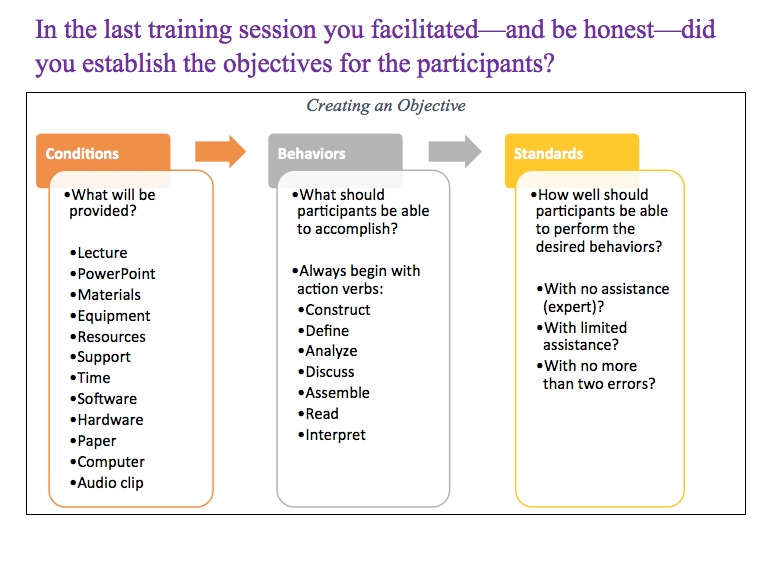

Now let’s talk about the training environment. If early in a training event, we establish expectations for the audience, we provide the clarity of what participants should anticipate; what they will be doing with the information; and how they may apply the course content to a work setting. In training, we call that establishing the objectives. Objectives give us the conditions—what is provided to perform the activity or to participate. Behaviors reflect the actions a participant is expected to demonstrate. The best behaviors always begin with an action verb, e.g., construct, evaluate, demonstrate, discuss. The final component of an objective is the standard. How well should the participants be able to perform the expected behaviors? Should they be experts or should they be allowed assistance from a facilitator or leader? Objectives clearly prepare the participant for the activity and establish the quality and quantity of the desired outcomes. If facilitators are true in communicating comprehensive objectives, they will see a marked improvement in class engagement and knowledge retention. Objectives establish the expectations.

Expectations and Leadership Style

More than 25 years ago, Dr. Paul Hershey (Hersey, P. & Blanchard, K. (1988). Management and Organizational Behavior. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ) created the situational leadership model that continues to guide leaders in establishing expectations for their staff. I often have used the model in succession planning, leadership education, and coaching relationships with leaders. The model brings clarity in determining an employee’s readiness level (technical skills) to perform a task and the employee’s confidence and willingness to perform the task. Based on this brief assessment, the model guides leaders toward one of four leadership styles he or she should employ. I teach a four-hour session on the concept and leaders often provide feedback that the model enabled them to zero in on performance challenges, better establish expectations, and modify their leadership approach.

Who Has Responsibility for Hosting the Expectations Conversation?

I often share with employees that if expectations are not clear, they seek out the leader and start the expectation conversation. While leaders have ownership in providing guidance and feedback, they get busy and may fall into the trap of believing an earlier discussion was sufficient. Staff has ownership for meeting performance requirements. If those requirements are vague, ambiguous, or were never established, staff should meet with the leader and host an expectations conversation. The conversation can be as short as five minutes. A good practice would be to schedule short, periodic, one-on-one meetings. An even better practice is to document the content of the meeting so both parties will have a clear and memorialized record of expectations.

So how many years has it been since you had an expectations conversation with your boss or staff? Did the conversation revolve around the level of autonomy and decision-making authority given for the task or responsibility? Did both parties leave the meeting knowing precisely what was expected and how far they could move with the task or responsibility? In the last training session you facilitated—and be honest—did you establish objectives for the participants? Probably not. Taking the five minutes, or less, to prepare employees and participants is the difference between disappointment and mediocrity or success and excellence. Make that small investment, and you may be surprised at the positive results.

Abel Hernandez, Jr., is a senior Performance Management consultant and corporate coach/leadership development at CareSource University.