Employees on the fast track increasingly are seeking “high-potential” career tracks. They and their employers realize such programs not only advance careers, but also advance companies by increasing employee engagement and improving the retention of top talent.

“This represents a shift in awareness among employers and employees of the value of high-potential programs,” explains Claudia Hill, global lead of high-potential development for Korn Ferry.

A recent study by Korn Ferry found that 97 percent of high-potential employees—those with the skills and aptitude to move up at least two levels within an organization—looked for high-potential programs when seeking new employment. In a related study in 2013, 77 percent of high-potential leaders said identifying highpotentials was important.

IDENTIFICATION INCREASES ENGAGEMENT

“Once high-potential employees are recognized, they always step up,” believes Azim Jamal, founder and CEO of corporate coaching enterprise Corporate Sufi Worldwide Inc. In his experience coaching high potentials at banks and IT companies, “they gain new ideas, as well as more training and exposure. They become better at time management and clearer in their priorities,” because of the extra challenges and attention.

Identifying employees as having high potential acknowledges their contributions to the company, validates what they are doing, and inspires them, Jamal adds. “Recognizing high potentials also inspires others to shine their own lights…to step up.”

There can be a downside, though. “Those not formally identified as high potentials report they are more likely to seek alternative employment in the near term than those in high-potential programs,” Hill says. That’s one of the reasons that 63 percent of respondents in the Korn Ferry survey don’t tell employees they are considered to be high potentials.

PARTICIPATION MEANS CHALLENGES

Being labeled “high potential” shouldn’t be a reward or an entitlement, Hill stresses. Programs with that connotation subtly sabotage themselves. Instead, she explains, “high potentials are expected to work harder and take on more challenges.” That must be communicated clearly if a program is to succeed.

“Specifically, the ‘high-potential’ label connotes a high level of performance, augmented by the willing – ness and capacity to grow. It means that at this moment, you have the capacity and drive to take on more complex roles,” Hill emphasizes.

That capacity and drive may change over time, so employees who aren’t there now need a pathway to guide them toward maximizing their potential. That pathway should be based upon common definitions and expectations, and should include managers trained to engage and encourage talent without minimizing the successes of those not in the high-potential program, Jamal points out.

When that infrastructure is in place, then companies can openly discuss high-potential programs. “Choosing to be transparent is a question of timing,” Hill points out.

HOLD CANDID DISCUSSIONS

Global technology distributor Avnet Inc.’s infrastructure, for example, developed gradually, beginning with those reporting to the C-suite. Now it goes several levels deeper, connecting local and regional development initiatives to its high-potential program.

“We encourage candid, ongoing discussions with all our employees about their performance and potential career desires,” says MaryAnn Miller, senior vice president, chief human resources officer and corporate communications, Avnet, Inc. “Individual learning agility, as well as performance over time and across various jobs, projects, and teams is a key consideration in defining our high-potential employees.

“As our process has matured, we have established more consistency in our assessment process,” Miller observes. The increased confidence that resulted enabled Avnet to talk with its employees about their performance and how their strengths can enable their career progression. “Giving high-potential employees candid feedback about how they are viewed and what they can expect in their careers inspires them to even higher levels of performance and engagement,” Miller says.

Because employees often identify influential positions as their career goals, Avnet began identifying the foundational experiences needed to prepare people for those positions. “By sharing the experiential requirements and discussing employees’ potential, they can broaden their perspectives of opportunities and see where they may be well-suited to grow and succeed,” Miller says.

CLEAR OBSTACLES

The development path sometimes is dotted with incumbents in key positions who are not seen as long-term successors to next-level executives. When that happens, rather than block the advancement of high potentials, Miller says, “we can discuss how incumbents’ skills can contribute in new ways to provide meaningful growth opportunities. This lets us reserve key pipeline roles for high-potential talent to gain the experience for future succession.”

Although high-potential employees are quick learners, they may not always succeed. “Not performing at a certain level in the high-potential program isn’t a reason to overlook those individuals for promotions or assignments,” Jamal says, but it may be a reason to slow their advancement or transition them to other projects or roles. For example, he adds, “Being an outstanding soccer goalie doesn’t mean you’ll succeed as a center forward or vice versa.”

Business is no different. Part of the issue is ensuring people are ready for the new challenge. “People in this phase of their careers are pressured to grow rapidly, so look at how you’re supporting them as they take on more and more complex roles,” Hill says.

In large companies, Korn Ferry reports, people in highpotential programs face special assignments, lateral moves, and promotions every 18 months on average. Because major transitions occur so frequently, this group has different needs than others in the organization.

“Their agility can work against them,” Hill points out. “They’re strong and fast learners who often have difficulty letting go of previous tasks, so they continue to fulfill them.”

And while they have large networks, the relationships rarely are deep, leaving them to sometimes lose track of their mission within the organization.

Corporate Sufi addresses this with coaching. As Jamal says, “High potentials often receive coaching with me directly, either individually or in a group, to recognize their contributions or to prepare them to take higher leadership roles.”

IDENTIFY LEADERS EARLY

Senior leaders are expected to be developed earlier and earlier in their careers. “One report says it takes about 15 years to develop senior leadership today—half the time of only a few years ago,” Hill recalls. Therefore, organizations need to look deeply to identify employees in their 20s and 30s with the drive and capability to take on more complex roles.

Identifying future leaders earlier doesn’t guarantee that each high-potential employee will succeed, but it does provide the organization options by ensuring that a broad talent pool gains the experiences needed to one day guide the enterprise.

CHALLENGES FOR HIGH POTENTIALS

According to Claudia Hill, global lead of high-potential development for Korn Ferry, after multiple moves in short succession, high potentials often have difficulty:

- CONNECTING TO THE FIRM ON A MISSION LEVEL. They often have no solid, long-term relationships with key managers or mentors who can remind them why they’re doing what they’re doing.

- MAINTAINING SOCIAL NETWORKS. They tend to have lots of shallow connections and need to know how to deepen them and maintain them as they move throughout the organization.

- ACQUIRING KNOWLEDGE FAST ENOUGH. They learn quickly, but just as they become comfortable in a job, they’re often transferred.

- MAINTAINING A VISION OF THEIR FUTURE. They bounce in and out of jobs throughout the company, first in their functional areas and later in general management, so maintaining a clear vision of their career path is challenging

THE BETTER THAN MONEYBALL WAY TO HANG ONTO HIGH-POTENTIAL TALENT

By Stephanie Neal, Research Associate, DDI’s Center for Analytics and Behavioral Research

There’s no doubt that Billy Beane, the subject of best-selling book and movie Moneyball, helped revolutionize baseball. As the general manager of the Oakland Athletics, he used data and metrics to make talent decisions at a time when other teams’ general managers and scouts relied on instinct and experience to identify promising players. His approach, predicated on picking up overlooked talent, turned the A’s into a team capable of competing with the biggest names in the sport—but with one big problem: turnover. The A’s approach found the talent needed to increase their wins, yet they couldn’t hang onto their valuable players.

How can you do better than Moneyball when it comes to your high-potential talent? Focus on retention. Once you have a system for identifying the leaders who are likely to make the strongest contribution to your organization, and to whom you plan to dedicate the biggest proportion of resources, you face the dilemma of recruiting too many or too few players into your program.

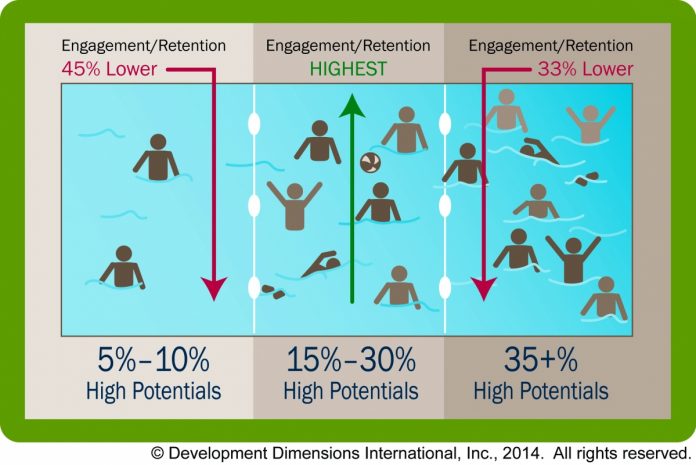

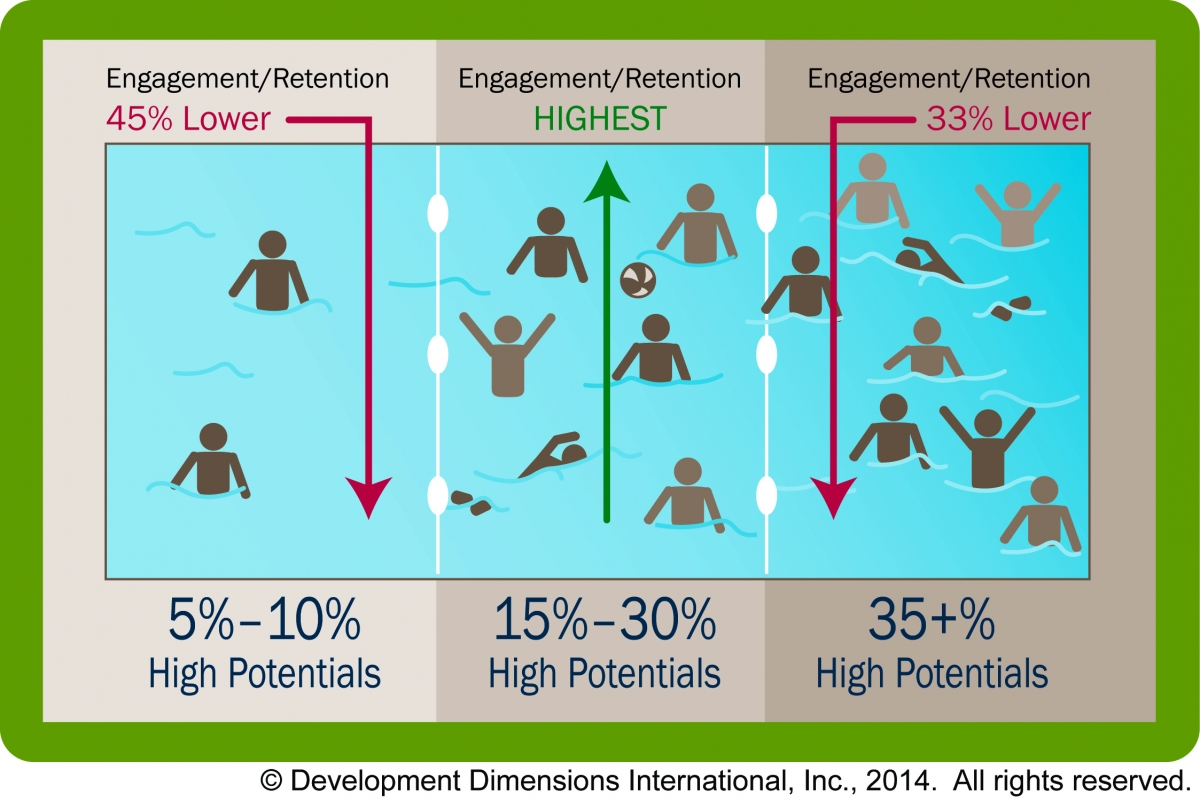

As part of the analyses we conducted for the Global Leadership Forecast 2014|2015 study, which was co-sponsored by DDI and The Conference Board, we sought to determine what size pool maximizes high-potential retention. To do so, we examined responses from more than 6,300 high-potential leaders.

We found that organizations with a larger pool of high potentials (35-plus percent) risk lower levels of engagement and retention (by 33 percent) than those with a more moderately sized pool (with 15 to 30 percent high potentials). This is likely because resources are being spread too thin across a larger number of leaders. Crowding the pool increases the risk of turnover, but even worse is having too small a number of high potentials. Organizations with the fewest high-potential leaders (5 to 10 percent) had the poorest retention and engagement rates of all (45 percent lower than the middle group).

Having too few leaders in a program might not seem like a problem, but if the program is too small, chances are it isn’t getting the support it needs. High-potential leaders who indicated their programs were weakly supported were twice as likely to indicate an intention to leave their organization within 12 months (16 percent), whereas only 8 percent of those with strongly supported programs (half as many) did.

Organizations with strongly supported programs do more for high potentials—in fact, we found that those with higher-quality programs are more likely to do these three things:

- Collect objective assessment data on high potentials’ capabilities, potential, and readiness.

- Have a mentoring/coaching program for high-potential leaders.

- Carefully evaluate high-potentials’ performance in developmental assignments.

It’s no surprise that each of these practices matters in building a sustainable and successful high-potential program. As we’ve learned from the Oakland A’s example, having a great system for identifying high potentials is not enough. Like Billy Beane did, you should use smarter data and metrics to scout and develop your high-potential talent, but you need to continue to monitor and support your most valuable players in order to hang onto them.

WHO ARE THE LINDSEY VONNS OF YOUR ORGANIZATION?

By Shani Magosky, Talent Management Consultant and Executive Coach, Vitesse Consulting

The 2015 FIS Alpine World Ski Championships in February featured Olympic gold medalist and World Cup champion Lindsey Vonn. With all of her accolades and success, imagine if her parents and coaches hadn’t told her early on that she had such potential. Imagine if Vonn had been left in the dark about the rationale for home schooling or moving away from family in Minnesota to Vail. Absurd, right? Of course, it made sense for her to be fully aware of and aligned with those big goals for her future.

Well, now let’s consider that scenario in the organizational realm. Are you still keeping the identities of your high-potential (“hi-po”) employees close to the vest? If so, 1985 called and wants its management style back (along with its one-piece ski suit). In 2015, we are deep into the era of transparency and proactive people development, and I encourage leaders to communicate to top performers their status as such and then support them with coaching.

Coaching high potentials serves a variety of purposes. First, it helps mitigate some of the tenuous reasons frequently vocalized against notifying high potentials, such as idealistic expectations of compensation or promotions, ego issues, or getting lazy. A good executive coach will help keep these performers focused on results and the bigger picture.

The positive impacts of coaching in the context of grooming hi-pos within a succession plan are far more significant not only for hi-pos but also the organization as a whole. To name a few:

INCREASE ENGAGEMENT, LOYALTY, AND RETENTION. Working with a coach is considered a privilege and sign that an organization values people enough to invest in their growth and development. One of the biggest influencers of retention is making people feel valued and connected.

TURN GOOD AND BETTER INTO BEST MORE OFTEN. Even the most talented, driven, and successful people get stuck sometimes or can up their game even further. A coach will continually challenge hi-pos to reach higher peaks, help them prioritize in service of completing the highest impact activities, and set up an accountability structure that works.

EXPEDITE FOCUS ON DEVELOPMENT AREAS. A coach not only works with the hi-po, but is also responsible to the hi-po’s sponsor and/or manager for addressing development areas identified as essential for continued career progression. Development needs may be areas for improvement that surfaced in performance reviews or may involve gaining experience in new functional or geographic areas. Either way, a coach serves as a confidential and objective partner who is focused on accelerating the hi-po’s success.

While an argument always can be made that anyone is replaceable, both the quantifiable and intangible costs of turnover are highest for this group. So tell your high potentials…or another company will.