The hybrid work environment has been presented as a healthy alternative to full-time in-office or full-time at-home work. However, it’s possible there are negative impacts from hybrid work, and that those negative impacts are falling on women more than men.

New research published last week by health insurer Vitality reveals that women’s health and well-being is suffering more than that of their male counterparts in a hybrid work world.

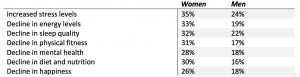

The survey of 2,005 UK office workers found that more than a third of women (35 percent) reported increased stress levels compared to men (24 percent), with more women reporting a decline in mental health (28 percent vs. 18 percent) and physical fitness (31 percent vs. 17 percent).

Vitality wonders if this may be why more women (71 percent) than men (53 percent) are calling for even greater flexibility in how and where they work as a way to improve their health and well-being in the future. Of those surveyed, more than two-fifths (46 percent) of women say they would be willing to quit their job if their employer didn’t prioritize their health and well-being as part of a hybrid working approach, indicating that they are holding their employer to higher account.

Working Harder Than Ever

This isn’t terribly surprising to me, given my own experience and observation. When at home, my work starts later, but also ends later. Without the natural exercise of walking to and from the office, I find I need a much longer break in the middle of the day to fit into that time slot everything outside the apartment that I used to do over the span of a whole day. That means exercising and errands all within that lunch break. I then find myself working later to make up for that time lost, and also working later because with no 40-minute walk home, I feel that I should use that freed-up time to finish tasks on my to-do list. In the era of quiet quitting by pulling back on work, I find myself working harder than ever. I suspect many other people are experiencing the same. I wonder whether more women than men are experiencing the greater, rather than relieved, post-pandemic workload.

Women at home means women in the place where they are known to do more work than their male counterparts, even when both are working. It stands to reason then that if the woman is working at home, ever greater home-related tasks will be thrown at her because she happens to be there. Children or spouse may come to her and ask her to do things they would have taken care of on their own if she had been at the office.

I often wonder what my mother, who passed away in 2013, would have thought of working from home. She had a career as a healthcare executive in hospitals, which she loved. In addition to the work itself, it seemed that my mother loved time away from the house, interacting with co-workers in the office. I suspect that the isolation from colleagues while at home would have produced a depressive effect in her.

Long commutes are a hassle anyone would be glad to be rid of, but what about the people who did not have long commutes—those like my mother, who had about a 20-minute drive to the office, or, like myself, a 40-minute walk? With no commute to be spared of, is working from home all, or part, of the time, still the healthiest option?

Higher Levels of Depression

A paper published by Frontiers in Sociology found that, indeed, women working from home were more likely to experience depression than women working outside the home. “We found that women working from home did experience higher levels of depressive symptoms than women working outside of the home,” authors Emily Burn, Giulia Tattarini, Iestyn Williams, Linda Lombi, and Nicola Kay Gale write. Their paper explores possible factors (social contact, exercise, and caring for children) that may contribute to an increased prevalence of depression for women who worked from home.

Yet, interestingly, women more than men say they prefer to work from home, according to a FlexJobs study from May 2021. How can that be explained? Many women were raised by stay-at-home mothers in a society that taught them the best place for a woman was in the home. In the 1980s, I was one of the relatively few children whose mother was a professional other than a nurse or teacher who worked outside of the home. When a woman who was raised with the example and messaging that home is the best place for her has the opportunity to do professional work from that best place, it must seem like an ideal solution. That’s one hypothesis to explain why women like something that seems not to be good for many of them.

It looks like few of us will be going back to the office full-time—ever. If we’re going to work all, or most, of the time from home, how can we offset the downside impact on physical and mental health? As we all know, what we like isn’t always what’s good for us.

Is your organization studying the impact of hybrid work on employee well-being? What have you discovered?