Chasing the Elusive 70 Percent of Learning that Happens via Experience

By Scott Millward, Chief Learning Officer, Farmers Insurance

I’ve enjoyed many fascinating conversations with my Learning and Development (L&D) colleagues over the years about the nature of the so-called 70-20-10 rule, which posits that individuals obtain 70 percent of their knowledge from job-related experiences, 20 percent from interactions with others, and 10 percent from formal educational events. We have had spirited debates over which modality is likely to produce the best results, what the true percentages ought to be, and if there are actually four, or five, or more ways to think about how adults engage in learning. I’ve often tried to articulate a position in these discussions that typically earns me a look—head cocked to the side, a knowing smile, and a patronizing chuckle. I believe that instead of focusing on the right balance of learning modalities, or perfectly matching content to situations “just in time,” L&D professionals should be solely concerned with creating a mindset that EVERY experience is learning.

This isn’t a new argument (dating back to at least Socrates 469-399 BC), and it isn’t that tough to take a position that creating better learners is a worthwhile pursuit. The rebuttals I have heard from my colleagues often center on statements such as: “Good luck with that. Let us know when you figure it out!” Or even more disheartening: “Well, that is a nice idea, but then they wouldn’t really need us would they?”

It is a true paradigm shift for some to think about learning as a purely individual way of experiencing the world, as opposed to something that is created for us. This is different from learnercentered design, which seeks to shape the experiences of a person to be more digestible or memorable. It is much closer to Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. If we have an intention to learn and a capacity to create personal meaning from an experience, then suddenly everything becomes an opportunity to learn. I like to think of this state of mind as a little like Neo becoming aware of the matrix in the movie, The Matrix. More recently, research from the Center for Creative Leadership and others has referred to this ability as “learning agility.”

Let’s tackle the first challenge of “It’s too hard.” True, it’s not easy to get people to think critically about the experiences they need in order to build a strong learning agility muscle. Employees are more pressured than ever to deliver results with less time and fewer resources. Given the reality of this situation, a prudent first step is to find ways to put context around experiences at work so there is an expectation that learning is occurring.

A Learning Experience: ProjectexChange

At Farmers, we have begun to create this environment using ProjectexChange, a simple piece of software that enables experience sponsors to post opportunities for experience seekers. Our first version is akin to a marketplace of shortterm projects that participants must apply to be a part of.

Projects are time bound, clearly articulated, and include likely areas of learning provided from a list of competencies. Prior to participation, sponsors and participants alike must attend a briefing outlining the goal of the ProjectexChange as a learning experience for all involved. This ensures that the intention to learn is expected. Once a participant is selected for a given project, the software defaults to a series of automatic prompts at regular intervals during the project period, the purpose of which is to document learning objectives and reflect on insights gained. Meetings also are held with the sponsor and participant at the beginning and end of the project to help articulate the value of the experience to the individuals and the company.

The ProjectexChange is only one way to embed expectations that learning should occur during everyday experiences and create space for the reflection necessary to solidify the learning. L&D functions must find other ways to shift the narrative from learning at the individual level as a “nice to have” to learning as an organizational way of life. Focusing on how to create better training environments and better modalities for carrying teachable moments to employees is unlikely to create a sea change in this conversation.

As for the second challenge, the “What about us?” argument, the reply seems self-evident. Learning and Development professionals also must learn to treat everything as learning. In one sense, how our profession adds the most value to an organization requires us to relinquish ownership over the learning process itself. We live in an era where there are no more unanswered questions, only things we have yet to Google. In this environment, knowledge is a cheap commodity. The role of the Learning professional evolves and looks more like a combination of a Sherpa, personal trainer, and that friend who always drags you to a new restaurant.

Results

So how did ProjectexChange work out for us? In short, it is a promising experiment.

Sponsors told us, “This tool has great potential in helping people with their personal development and exposure to other departments.”

Sponsors also gave us good feedback: “Sponsors need to be realistic about time commitments, so players can balance their development project with regular work.”

Project players shared that they were able to develop new relationships, morale was heightened, and the organization would benefit from greater use of the approach.

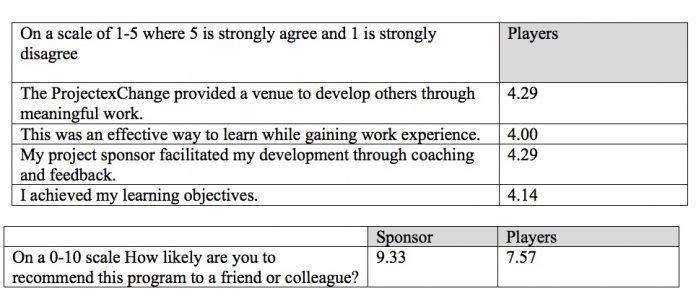

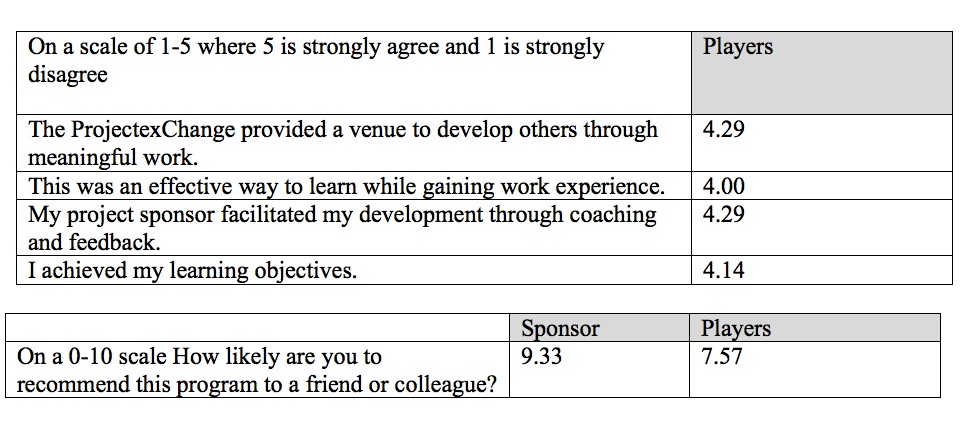

Our data points further validated a positive first step. From participant perspectives:

Helping people consistently create their own learning moments is not easy. As with most difficult challenges, overcoming them requires focus and experimentation. Efforts like the ProjectexChange are a necessary first step to furthering the dialogue about the future role of Learning and Development.

The Adaptive Learner: Building Innovation Skills Through Instructional Design

By Douglas Lieberman, Thought Leader, Instructional Design, and Matthew Valencius, Manager, Instructional Design & Development, IBM Center for Advanced Learning

As your Learning team is called upon to do more faster, is the lifecycle of your learning programs growing shorter? Do you find yourself wondering how your learning designs will make a difference as shorter learning durations steal the time needed for solid skill building? These are questions we’ve asked ourselves at IBM. And we think we’ve found a solution to the dilemma of opposing positives: agile responsiveness vs. immersive skill building.

The answer revolves around innovation. Every tech company wants its employees to be innovative. The trick is recognizing that innovation is a skill—one that can be developed in different ways across many short learning experiences so that, over time, the outcome is a more innovative workforce. IBM Learning aims to “make every IBMer an innovator” using a suite of instructional design methods founded in cognitive science, enabling our employees to respond more swiftly, flexibly, and creatively to the changing technical and business landscape.

To accomplish this, we’ve built a learning design tool kit called The Adaptive Learner, based on meta-analysis of the substantial body of research on innovation. This tool kit is founded on the premise that innovation, a teachable skill, depends largely on lateral thinking, combining existing ideas across seemingly unrelated realms to create something new and useful. We categorized the research we examined into five behaviors that support innovative thinking, then developed instructional design techniques that can infuse those behaviors into learning events on any subject taught in any medium. The five behaviors are:

1. Strategic Intuition: The act of combining seemingly unrelated ideas to create something new and useful. The term was popularized by William Duggan of Columbia Business School, although others also have examined this behavior (for example, Jeffrey Dyer, Hal Gregersen, and Clayton Christensen’s “associational thinking”). IBM learning designers use this idea to create a new kind of case study that requires learners to deconstruct multiple approaches to a problem from diverse industries, then experiment with unexpected combinations to uncover fresh solutions.

2. Social Connectivity: The act of networking across silos, which is crucial for uncovering relationships, new ideas, and constructive feedback. To help learners practice this behavior, our learning designers write exercises that assemble heterogeneous groups of learners, both face-to-face and through electronic media, and require them to engage in cross-silo communication that facilitates lateral thinking.

3. Exploration: Identifying unseen problems and opportunities, then testing potential solutions. Learning designers create exercises that invite learners first to invent their own approaches and then evaluate them against existing practices. Learners gain confidence in their ability to improve standard methods, while weighing those improvements against real-world criteria to ensure their suitability and effectiveness.

4. Flexibility: Quickly and appropriately adapting to change, success, and failure. Learning designers teach this through exercises in which the rules shift partway through, resulting from fictional client demands, new developments, or failures in negotiation or technology. Learners learn to keep their balance and solve problems during times of change.

5. Drive: Fearlessly taking action with a sense of urgency, even when it is potentially disruptive. Learning designers develop exercises that are demanding and time-limited, but that either deliberately omit information or make uncovering it risky and difficult. Even though learners are racing against the clock, they cannot succeed until they identify what is missing and incorporate it into their results.

Early evaluation of The Adaptive Learner initiative suggests that it works. For example, when we quizzed learners on scenarios that test lateral thinking, before and after participating in learning events that employ Adaptive Learner instructional design, the number of learners who made innovative decisions rose by 24 percent. And when the same learners were evaluated for self-efficacy in lateral thinking, a majority of them scored highly enough to predict an increase in innovative behavior in the workplace.

More work needs to be done. Cognitive scientists have, for example, found connections between innovative thinking and role-play improvisation, the detection of unexpected affordances, and the probing of inconsistencies or contradictions. Innovation is an enduring and valuable skill we can all strengthen. We can do it faster through careful design across our learning portfolio. As we refine our approach, we continue looking for new research and ideas. Is there something you can share?