Navigating complexity, demonstrating global expertise, identifying and predicting what diverse customers want and need, driving continuous innovation, and leveraging global talent through cross-border collaboration! Add the fact that a 21st century leader’s success depends more than ever on virtual team leadership, and you soon realize a machine is not going to be doing this job anytime soon.

Here are some guidelines for virtual team leadership:

1. Ability to communicate readiness: A racecar driver visualizes the track before a race, knows his or her strengths and vulnerabilities, and analyzes potential “what ifs” such as weather changes. The virtual team leader should do the same. Virtual global teams have many barriers to performance, such as different time zones, reporting relationships, and loyalties, plus cultural differences. As Shakespeare said in Hamlet, “Readiness is all.” Readiness demonstrates a leader’s credibility and fends off early stage skepticism.

2. Ability to instill trust and purpose: Water is necessary to sustain life, but it is not sufficient. On virtual teams, trust is required to sustain the life of the team and overcome challenges such as isolation, fragmentation, and confusion. For high performance, trust must be powered with purpose. In his new book, “Team of Teams,” General Stanley McChrystal says, “A fighting force with good individual training, a solid handbook, and a sound strategy can execute a plan efficiently, and as long as the environment remains fairly static, odds of success are high. But a team fused by trust and purpose is much more potent. Such a group can improvise a coordinated response to dynamic, real-time developments.”

3. Ability to be clear: Too much confusion on a virtual team sends it spiraling into dysfunction. Virtual leaders must strive for clarity and precision in their own communications, and make a nuisance of themselves by challenging vague language and implicit assumptions. Not wanting to be too heavy-handed, a virtual leader might let some fuzziness go by. On a virtual team, that is inviting chaos in through the front and back doors, as well as the windows.

4. Ability to maintain virtual presence: No matter how much you clarify a virtual team’s goals, objectives, tasks, and processes, it will never be enough. As a project progresses, there will be further clarifications to be made, unforeseen problems that need new thinking, new circumstances that emerge, and different team members coming in and going out. Enterprise collaboration and social networking technologies enable a virtual leader to be there with the team. The leader without a virtual presence creates uncertainty, which creates anxiety, which harms performance.

5. Ability to mind attention gaps and missing linkages: It’s not unusual for attention gaps to be present on virtual teams. Each member is situated in his or her own location, and has specific roles to play. Team interactions are more limited than on co-located teams, and communications tend to be leaner. It is easy for members to become preoccupied with their piece of the project puzzle, and fail to pay enough attention to critical information coming from elsewhere. Virtual leaders must put themselves in a prime position to identify and manage attention gaps and missing linkages as they occur.

6. Ability to be transparent: Nothing kills a virtual team faster than a lack of transparency, e.g., not sharing information across the team or having hidden agendas. Let the technology do the work. Social networking enables lots of information to be shared, and team members can filter out what is not important to them. Virtual leaders must be careful about assuming they know what the team needs, and when.

7. Ability to build virtual team spirit: It’s difficult to build a good team spirit by sending out a periodic e-mail. As Sebastian Bailey says in a Forbes article, “…virtual teams often feel like no more than globally dispersed individuals working on the same project.” Think people-centric, not technology-centric. Have personal check-ins at the beginning of meetings; share stories, not just facts. An inclusive and vibrant team culture is more important than technology.

8. Ability to communicate sufficient context: Every virtual team project has a context—why is it important to the business? Who are the major stakeholders and what are their expectations? What are the conditions members of the team face? If team members don’t understand the context, how can they act with intelligence?

9. Ability to give feedback to individuals, as well as the team: A common complaint of virtual team members is that they receive insufficient feedback (or none at all), or they only get feedback when something goes wrong. A virtual team leader is still responsible for giving constructive feedback and coaching even if the team members report directly to someone else. Also, some virtual leaders only give feedback to the team as a whole. Feedback to individuals is not only important for uncovering issues that might not be raised in team conversations, but for inclusion and engagement.

10. Ability to focus on outcomes: You cannot see what your team members are doing during the workday. You may not even be working at the same time. It’s easy to start assuming team members are “loafing” and slip into leader paranoia. You have to manage by performance outcomes. What was agreed to, and what was delivered. If you can, “keep eyes-on, hands-off.” Think effectiveness and fulfilment of purpose before efficiency.

11. Ability to negotiate shared operating agreements: It is important for virtual teams—particularly those with members from different cultures—to negotiate shared operating agreements, such as, “How will we make decisions or communicate?” Without them, the team will always be reinventing the wheel or be forced into following the majority approach. Not everything needs to be negotiated, just those team activities/processes that have a large impact on the success of the project.

12. Ability to plan virtual communications: Create a robust communication plan with the team that provides regularity of contact and a common view of the total project. Spontaneous communication by instant messaging is excellent for daily communications between individuals and even groups, but a virtual team needs to build a strong, binding identity and a shared understanding of where the project is and where it’s going. Ask:

- When will we connect as a whole team? Daily, weekly, bi-weekly? Create a drum-beat rhythm.

- How will we connect? What technology or technologies are best for us to use—for tasks and relationships?

- When will we connect? What time is most appropriate (accommodating for time zones)?

- How long should each meeting be? What duration allows us to be most productive?

- What must be covered in each meeting, and what is unnecessary? Can status updates be put on social media, and meetings used for collaborative problem solving?

- Who needs to be in the meeting? Everyone? Spokespeople from sub-teams? Stakeholders from outside the team?

13. Ability to surface and manage virtual conflict quickly: Conflict on virtual teams often lies beneath the surface of everyday interactions and becomes sneakily toxic. Virtual team leaders need sensitively attuned antennas to what is said, what is not said, and how something is said. Those in virtual conflict often don’t want to explore the conflict in a teleconference; they just want to get off the call as quickly as possible. You can address the conflict off-line with the individuals involved. If you don’t surface the conflict and deal with it quickly, it can fester in silence (become hyper-personal) and spread like a virus.

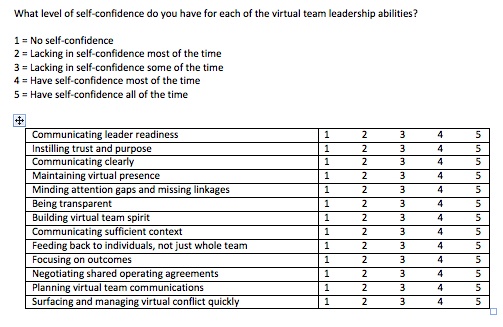

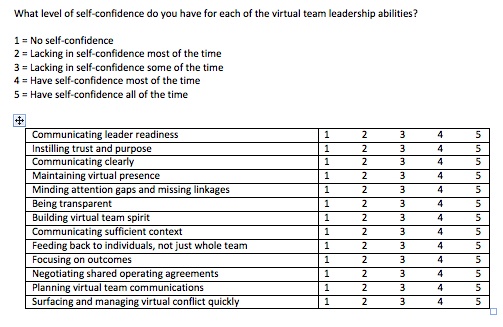

Here’s a quick way to evaluate your virtual team leadership abilities.

Terence Brake is the director of Learning & Innovation, TMA World (http://www.tmaworld.com/training-solutions/), which provides blended learning solutions for developing talent with borderless working capabilities. Brake specializes in the globalization process and organizational design, cross-cultural management, global leadership, transnational teamwork, and the borderless workplace. He has designed, developed, and delivered training programs for numerous Fortune 500 clients in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Brake is the author of six books on international management, including “Where in the World Is My Team?” (Wiley, 2009) and e-book “The Borderless Workplace.”