Organizations put huge amounts of time, money, and energy into delivering learning. But real insight into the impact that learning has on a company remains frustratingly elusive. Most companies do a good job of tracking who has completed what training, but that doesn’t tell much of a story, let alone help determine the effectiveness of learning.

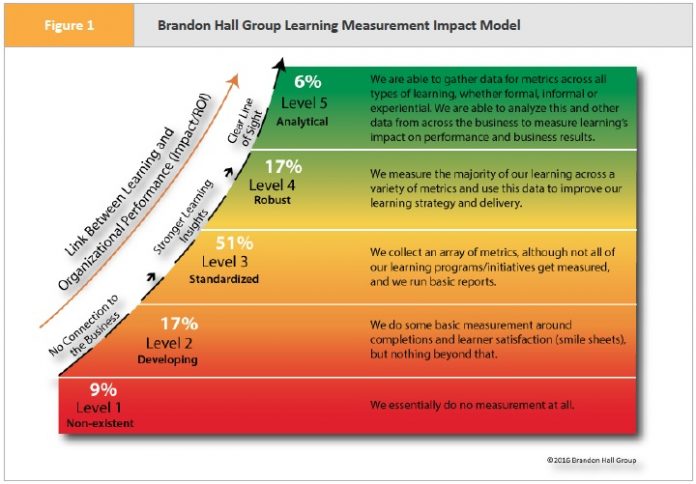

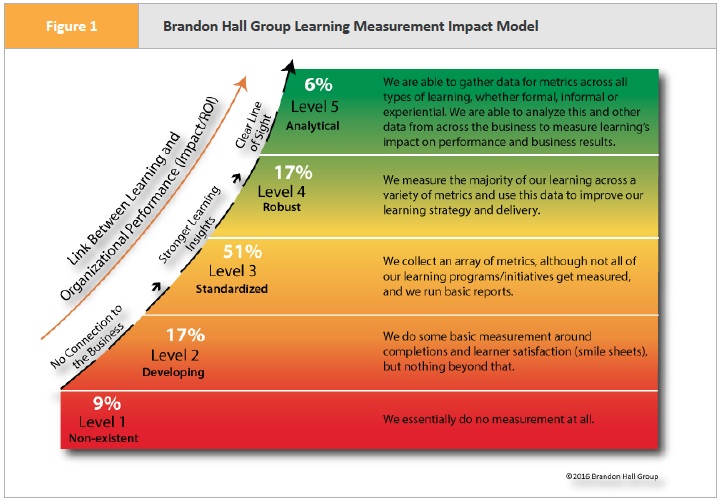

Brandon Hall Group’s 2016 Learning Measurement Study found that few organizations are collecting metrics that help link learning to organizational and individual performance. In fact, only 6 percent of companies are truly measuring all different types of learning with an eye on business results.

Brandon Hall Group’s Learning Measurement Impact Model illustrates the five levels of measurement maturity—Non-Existent, Developing, Standardized, Robust, and Analytical—and their attributes. It also shows the level of alignment between measurement and organizational performance at each level of measurement. More than 25 percent of survey respondents said they are doing only basic measurement or essentially no measurement of all. Approximately half are at what we call the Standardized level, where an array of metrics is collected and basic reports are run, but without much analysis or ability to link learning results to performance.

Source: 2016 Brandon Hall Group Learning Measurement Study (n=367)

This lack of measurement effectiveness is evidenced by the study results, which show that companies are not very good at measuring learning that is not formal in nature, and they rely far too heavily on basic metrics such as completion rates and smile sheets. This shortsightedness is keeping these companies from building learning into a strategic influencer of the business. The study also finds that organizations perhaps should not be so concerned with the specific ROI of learning, but rather learning’s impact on business outcomes.

So what is happening? Why is there such lackluster measurement from a part of the business that is so hungry for data? Much of this can be found in the results of this study, but the reality is that good measurement is difficult. It is why we see such a focus on completion rates and smile sheets. This data is easy to collect and understand, but it does not really tell us anything. What does it mean if 95 percent of the people enrolled in a course completed it? There is no way to extrapolate any sort of impact from this data.

The other harsh truth is that the Learning function traditionally doesn’t have the skill set in-house to make sense of all this data. In turn, Learning professionals rely heavily on their technology providers to give them the tools necessary to measure learning. But without even knowing what questions to ask, all of the data and tools in the world won’t help.

And this all applies to measuring the things companies have been doing for decades: formalized courses and classes. When it comes to newer types of learning methods and modalities, organizations are at a complete loss. Whether informal, experiential, informal, mobile, or gamified learning, companies are finding it that much more difficult to measure.

The rest of this article explores and analyzes the top findings of Brandon Hall Group’s 2016 Learning Measurement Study.

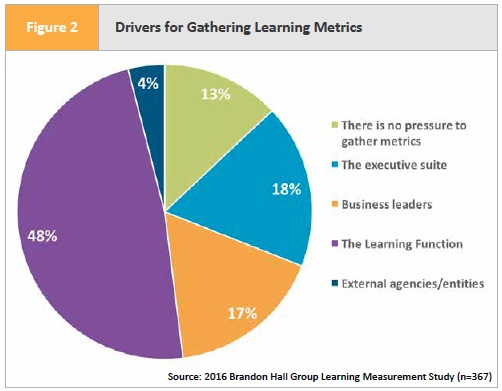

1. Most of the Need to Measure Learning Comes from Within the Learning Function. One of the ongoing challenges learning functions face is a need to demonstrate ROI in order to justify their existence. Companies want to know what kind of impact learning is having on the business. The conventional wisdom paints a picture of organizations demanding metrics and results that are notoriously hard to come by.

According to Brandon Hall Group’s 2016 Learning Measurement Study, however, there does not seem to be all that much pressure to measure learning, except from the Learning function itself.

Between executives and business leaders, internal, non-learning entities are driving metrics at only about one-third of companies. Another 4 percent say pressure for metrics come from outside the company, and 13 percent say they have no pressure to gather metrics at all. The rest of companies (nearly half overall) say the Learning function is driving the quest for metrics.

This doesn’t necessarily mean the executives and leaders of these companies are not interested in measurement, but they are not driving the conversation. If that is the case, the Learning leaders at these organizations had better have strong alignment with the rest of the business if they hope to measure the true impact of learning on the business.

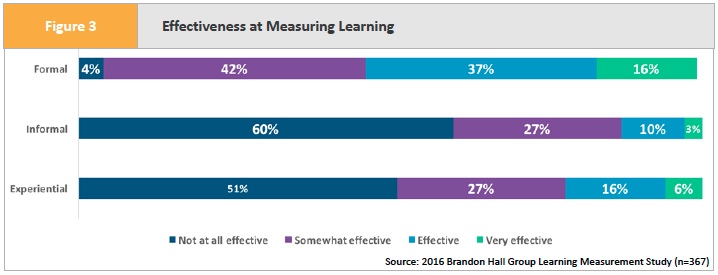

2. Companies are Struggling to Measure Informal and Experiential Learning. Organizations have gotten relatively good at delivering formal learning, since that is where their focus has predominantly been. So they typically are much better at measuring formal learning than they are at measuring informal and experiential learning.

Less than 4 percent of companies say they are not at all effective in measuring formal learning, but more than half say they aren’t any good at measuring informal or experiential learning. This is one of the major challenges organizations face when deploying a blended learning strategy. They feel they won’t be able to measure anything outside of the course or classroom, so they tend to shy away from doing it at all.

Organizations need to face two stark realities:

First, they aren’t even that good at measuring formal learning—the thing they are supposed to be really good at. More than 40 percent of organizations said they are only somewhat effective at measuring formal learning.

Second, the measurement of learning doesn’t really change because of the mode of delivery. There may be new and different data points, but what ultimately is being measured should remain the same—performance:

- Are learners acquiring the knowledge better than before?

- Are they getting to optimal productivity more quickly?

- Is the learning effectively addressing the challenge it was designed to improve?

If the measurement strategy is solid, the modality is almost irrelevant.

Exacerbating the challenges with measuring informal and experiential learning is that most organizations do not have a strategy in place for measuring these types of learning. Nearly 60 percent of companies have no strategy in place specifically for measuring informal or experiential learning. For those that do, most apply the same strategy across all learning types.

3. Few Companies Measure Beyond Kirkpatrick Levels 1 and 2. One of the most common ways in which organizations measure their learning is via the Kirkpatrick Model, which uses four levels of measurement. Approximately 83 percent of companies report using this model. Often, companies are using measurements that align with some or all of the levels in this model, but don’t even realize they are using it. In any case, our research shows that organizations may not be applying the model to the degree that is recommended by The Kirkpatrick Partners.

Level 1 is the easiest level to measure, often referred to as “smile sheets.” At this level, companies are just trying to find out if learners liked the learning experience. Being that it is the easiest to measure, the Kirkpatrick Partners recommend that 100 percent of learning programs be measured at this level. However, we see that just 54 percent of companies measure more than 75 percent of their learning at Level 1.

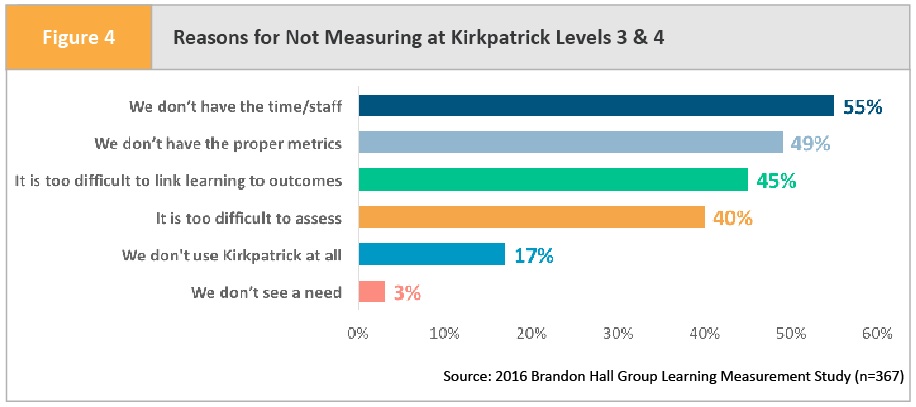

As we progress through the levels, the amount of measurement drops off dramatically until we reach a point where 40 percent of companies are not measuring at Level 4 at all. The recommendation at this level is to measure at least 10 percent of learning programs.

Obviously the type of measurement that occurs gets increasingly complex as the levels progress, and this is a big part of the reason why measurement tapers off. The biggest reason why companies aren’t measuring past Level 2 is a lack of time and/or staff.

Companies also complain that they do not have the right metrics and that it is too difficult to draw a straight line between learning efforts and business outcomes. However, only 3 percent of companies using the model don’t see a need to go beyond Level 2. That means the vast majority see the value in these measurements but are unable to get them done.

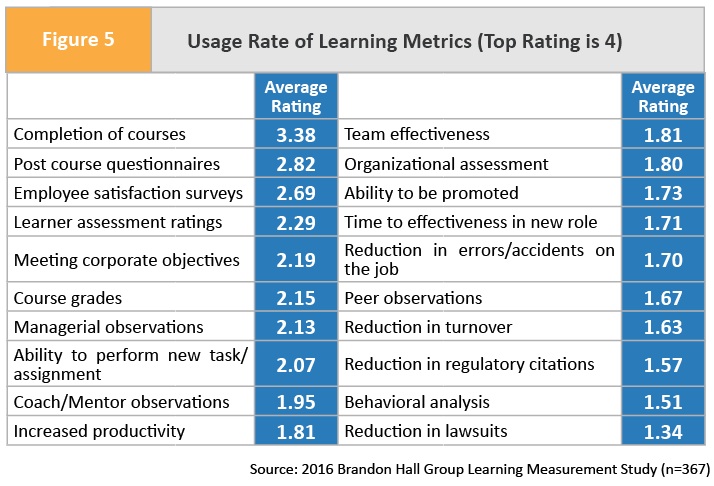

4. Organizations Use Mostly Basic Metrics and Few Outcomes to Measure Learning. We’ve seen through the application of the Kirkpatrick Model that organizations are mostly focused on basic measurement. This becomes crystal clear when we look at the actual metrics they are using. Ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 4, where 1 means it is not used at all, and 4 means it is used consistently.

Course completion is the No. 1 metric being used, and by a wide margin. This is clearly the easiest metric to gather, but it doesn’t really tell an organization much. If 98 percent of learners complete a course, you still have no idea if was effective, if they liked it, if they will remember it, or if it will help the business. The more strategic measurements are much further down the list, such as team effectiveness or time to effectiveness.

Speaking of effectiveness, even the organizations in the study—the ones that made course completions the No. 1 metric—don’t think it is the most effective. It’s not even in the top five. Coach observations, meeting corporate objectives, and the ability to perform new tasks all are seen as more effective metrics—they just aren’t used much.

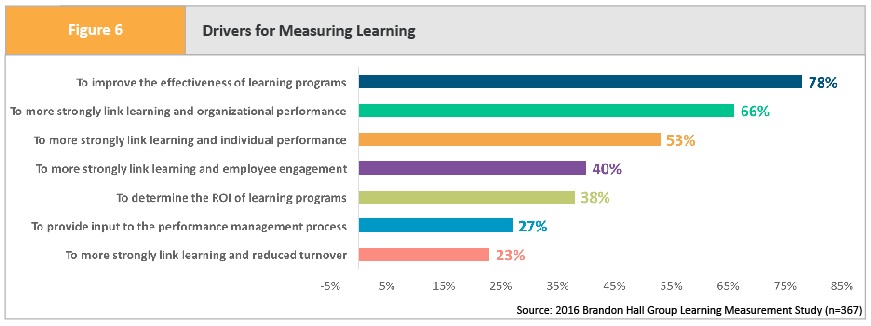

5. ROI Is Not a Top Driver of Measurement. Time and again we hear how the Learning function is expected to determine the ROI of its programs. However, as noted earlier, most of the pressure to measure learning does not come from executives or business leaders, but rather from the Learning function itself. Also, the majority of companies do not use business-based outcomes to measure learning, which would be a key part of determining ROI. Approximately two-thirds of companies say they do not consider revenue growth or profitability when measuring learning. Nearly three-quarters say they do not look at revenue per employee either.

When we look at the overall drivers for measuring learning, ROI ranks near the bottom.

Respondents could choose as many drivers from the list as they wished, and yet only 38 percent said that determining ROI is a main driver for measuring learning. Companies are far more focused on ensuring their programs are effective and having an impact on performance. Also, the survey found that 36 percent of companies are using the Phillips ROI model, also known as Level 5 in the Kirkpatrick/Phillips model, to measure learning.

In reality, more organizations should stop thinking in terms of ROI and begin thinking in terms of performance. Performance is the return, and it is not something that always translates exactly into dollars. But if Learning leaders can show the impact learning has on both individual and organizational performance, that goes a long way to justify current and future investment in learning programs.

David Wentworth is principal Learning analyst for Brandon Hall Group, a human capital management (HCM) research and advisory services firm that provides insights around key performance areas, including Learning and Development, Talent Management, Leadership Development, Talent Acquisition, and HR/Workforce Management. Please join us for our 3rd annual HCM Excellence Conference Jan. 24-27, 2017, in Palm Beach Gardens, FL.