Wondering if someone might be thinking of leaving your organization? Results from a survey conducted by The Ken Blanchard Companies have identified a potential early warning sign—a relationship between how often a person meets with his or her immediate manager and that person’s intention to remain with the organization.

In taking a deeper look at survey data presented in the article entitled “10 Performance Management Process Gaps” (Training magazine, July/August 2014), researchers compared the frequency with which people met with their immediate manager to five positive work intentions:

- The intention to perform at a high level

- The intention to apply discretionary effort as needed

- The intention to stay with the organization

- The intention to recommend the organization to others

- The intention to work collaboratively with others as a good organizational citizen

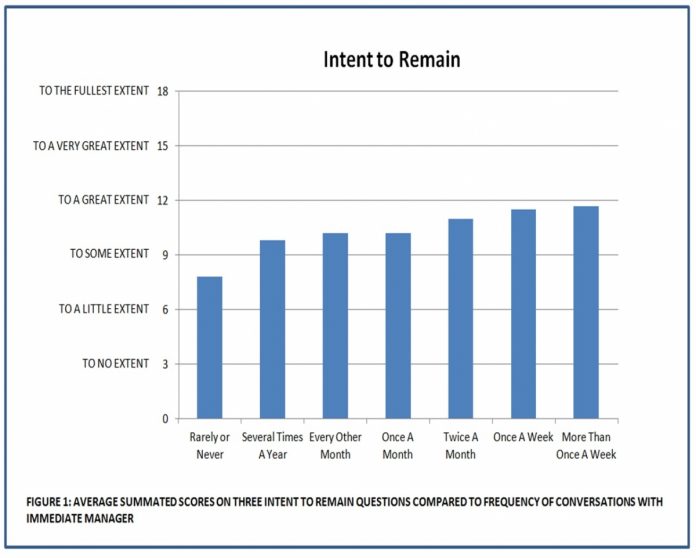

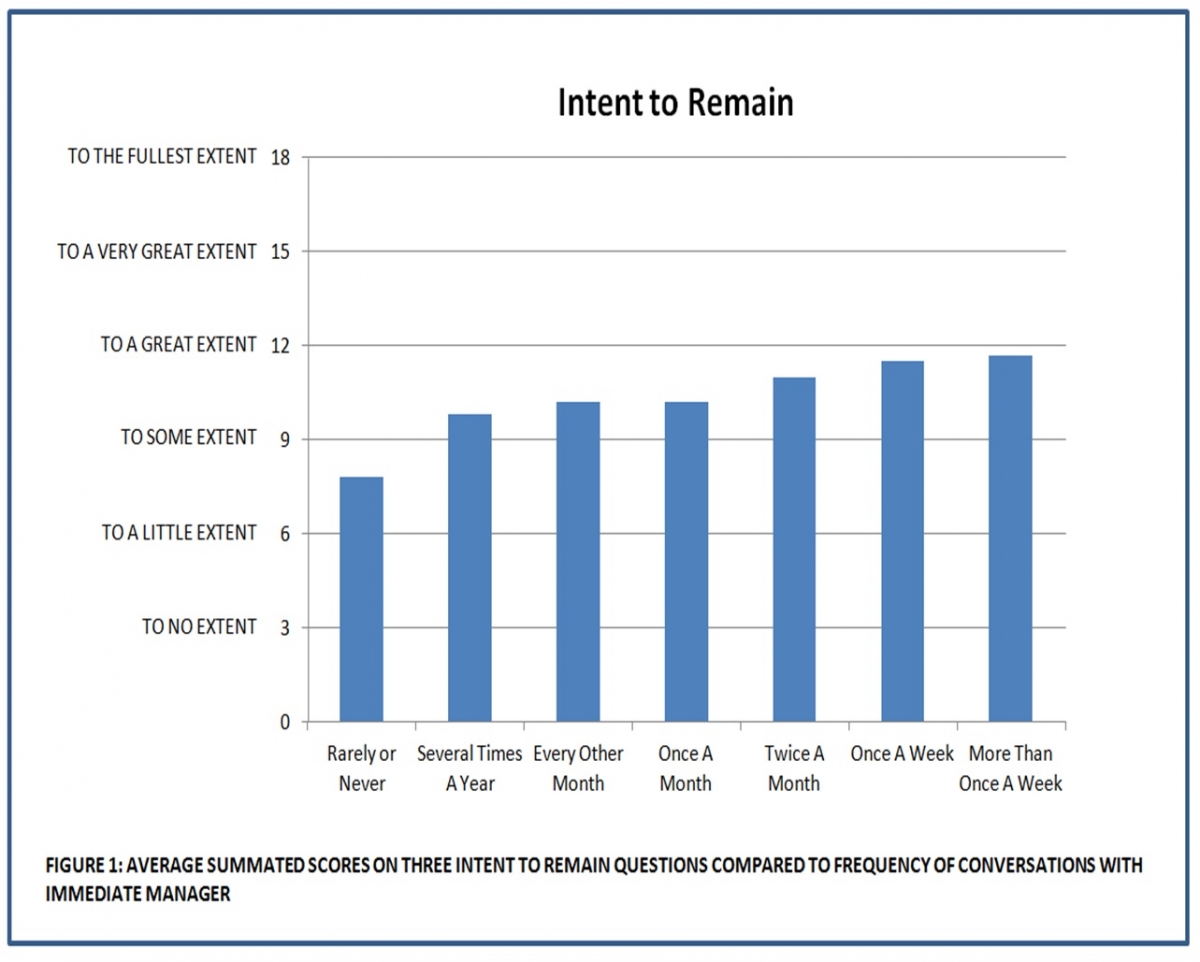

Using the summated score of three intent to remain questions, the researchers found that the more often respondents reported meeting with their managers, the greater extent they indicated that they intended to remain with the organization—even if offered a similar or slightly better job somewhere else. (See Figure 1: Intent to Remain graphic below).

This data point reinforces some of the experiences Blanchard consultants have had in their work with clients, including work with a national quick-service restaurant chain several years ago.

In reviewing retention rates among several locations in the chain, Blanchard consultants found that one location had much lower turnover than the chain’s national average. Follow-up conversations were held with the manager of that location to discover what he was doing to keep the rate so low. He shared something that proved to be unique. This manager said he made sure to take at least 10 minutes every week to talk to each employee. It wasn’t about job performance—it was just a conversation to check in with each person and see how things were going.

Intrigued by this response, Blanchard executive staff members conducted a small experiment that involved a group of 20 managers and their direct reports who worked in an office environment. They asked the managers in this focus group to spend the next six months conducting regular meetings with their direct reports. This meeting would be different from a performance review conversation. The manager would set the time for the recurring meeting, but the agenda of the meeting would be up to the employee.

At the end of the testing period, the Blanchard staff conducted interviews with the managers and the direct reports to find out about the effect the meetings may or may not have had on performance. They also scheduled time with each manager’s senior leader to see if the senior leader had noticed any change in performance.

The results were surprising in the way the perceptions differed. The senior leaders reported noticing an increased level of positive communication between the managers and their direct reports.

The managers, however, indicated that they felt the experiment was less than successful. As one manager shared, “I don’t know how helpful I was—we talked about many things, but I’m not sure I had that many answers. I don’t think I was as much help as my direct reports would have liked.”

Given the mixed results, the Blanchard staff members were interested to talk to the direct reports. Their responses bridged the gap between the perspectives of the managers and those of the senior leaders. As one direct report explained, “My manager doesn’t have all the answers, but he’s always there for me to discuss what I need and how to find it. I’ve never felt as supported as I have in the last six months.”

Other direct reports also shared their appreciation of their managers’ efforts and their belief that the recurrent meetings had created a closer relationship. This outcome was similar to the experience that had been reported by the restaurant chain employees.

TAKING AN EXTRA MINUTE

This experience—along with others like it—has been the basis over the years for the Blanchard Companies’ recommendation to clients to increase the frequency of one-on-one conversations between managers and direct reports. The company believes that day-to-day coaching is the one area on which managers should focus more effort.

Ken Blanchard, bestselling coauthor of “The New One- Minute Manager,” explains. “As a manager, you have to make the time to check in. The best minute you spend is always the one you spend on your people. Managers need to take an extra minute to set clear goals with each person and provide feedback in the form of One-Minute Praisings and One-Minute Re-Directs.”

According to Blanchard, managers achieve a triple benefit when they spend focused time with their people working through issues in need of attention. First, when managers make sure goals are clear in the beginning, it saves time and trouble down the road because it ensures employee efforts are directed and on target. Second, managers who provide needed direction and support help their people develop in their jobs so they can move to higher levels of autonomy. Third, when managers and direct reports spend time together, it creates a bond that taps into the human connection all people long for—and it encourages everyone’s best efforts.

“Frequent one-on-one meetings are a 1-2-3 combination that saves time in the long run,” says Blanchard. “People develop skills, achieve more, and become more self-directed. It’s a small investment in time that will pay big dividends over and over again.”

GARRY RIDGE AT WD-40 COMPANY

A great example of a leader who has embraced this more proactive management style is Garry Ridge, CEO of the WD-40 Company in San Diego. In addition to being the chief executive of the ubiquitous global brand, Ridge is also a co-author with Ken Blanchard on the book, “Helping People Win at Work.” Ridge’s philosophy is that leaders spend too much time evaluating performance and not enough time helping people succeed.

Ridge is a big believer in “no surprises” when it comes to expectations between managers and direct reports. In addition to regular one-on-ones, Ridge also implemented a policy of 90-day mini-performance reviews—a more formalized look at progress toward goals on a quarterly basis.

As Ridge explains, “In many organizations, after annual goals are agreed on, they are filed away in a drawer until the annual performance review a year later. Then they are taken out to compare an employee’s performance against them, with a manager grading the employee’s results. That’s crazy. Managers and team members need to be looking at goals much more often than that. If they don’t, there is a great chance of employees being ‘surprised’ at review time by finding out that their efforts have been off-mark or not prioritized properly. That’s not fair to the employee.

“At WD-40 Company, we hold managers and direct reports equally responsible for achieving a direct report’s goals. If a team member is receiving anything less than an ‘A’ rating, the first question I am going to ask is, ‘What has the manager been doing to help this team member succeed?’”

GETTING STARTED

For HR and organizational development (OD) leaders wondering about the level of communication in their organization and whether it is negatively affecting performance, here are a few questions and strategies to consider.

- How often are your managers currently meeting with their direct reports? Ken Blanchard recommends that managers meet with each person at least every other week for 15 to 20 minutes. The meeting doesn’t have to be long, but it is important that these one-on-ones occur on a consistent basis. Make sure that managers treat these meetings as seriously as they would treat meetings with their own supervising leader. Scheduling the meeting is the manager’s responsibility, but the direct report sets the agenda. Ensure that meetings are not postponed or canceled just because the manager believes there is nothing pressing to discuss.

- Make sure managers focus on the direct report’s agenda. Managers sometimes use one-on-one meetings to provide updates, discuss strategic objectives, or bring up other issues of interest to the manager. While that type of information sharing is important, the primary focus of these meetings should be the direct report’s agenda. What does the employee want to discuss? Where does he or she need help?

- Take a deeper look. In cases where managers and direct reports are not meeting as often as prescribed, probe for underlying root causes. Is the lower frequency a result of mutual agreement or is it a symptom of a relationship that is in trouble? Find out if the root cause of the issue is the manager’s lack of competence, commitment, a little of both, or something else. Set up a time to discuss the situation with a manager who is not taking the time to meet with his or her direct reports.

- Measure progress and praise improvement. The old adage, “What gets measured gets managed,” still applies. Implementing a new managerial practice requires patience. Old habits can be difficult to change—especially when the effect of a new approach is not easy to determine. Consider ways you can chart progress for managers who could use encouragement in adopting this new habit.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CONVERSATION

Performance management relies on effective one-on-one communication between managers and direct reports—including goal setting, day-to-day coaching, and measuring progress. The frequency and quality of conversations happening in an organization represent an important marker of the overall health of the company. Don’t let a lack of communication between managers and employees negatively affect performance in your organization. Start encouraging frequent, high-quality conversations today.

David Witt is a program director for The Ken Blanchard Companies and a former member of the company’s Office of the Future. He can be reached via www.kenblanchard.com.