Great leaders consistently accomplish the mission and take care of their team. To do so, leaders must stay laser focused on both. Unfortunately, on almost every team, there are individuals who make this very challenging, if not an impossibility, if we allow it. All leaders will more effectively be able to achieve those standards (accomplish the mission and take care of their team) if they understand and can assume the three roles of a leader: Commander, Coach, and Mentor (this is something a former teammate brought to us, but we are unsure of who that teammate was and of the origins of The Three Roles of a Leader).

Commanding is the act of giving direct orders in pursuit of mission accomplishment. Coaching is teaching our teammates the skills they need to succeed—the “X’s and O’s” of how we do things. This could be blocking and tackling in football, sales techniques in the corporate world, or shooting and close-combat techniques in the military. Mentoring is about building a culture and teaching our teammates what it means to be “one of us.”

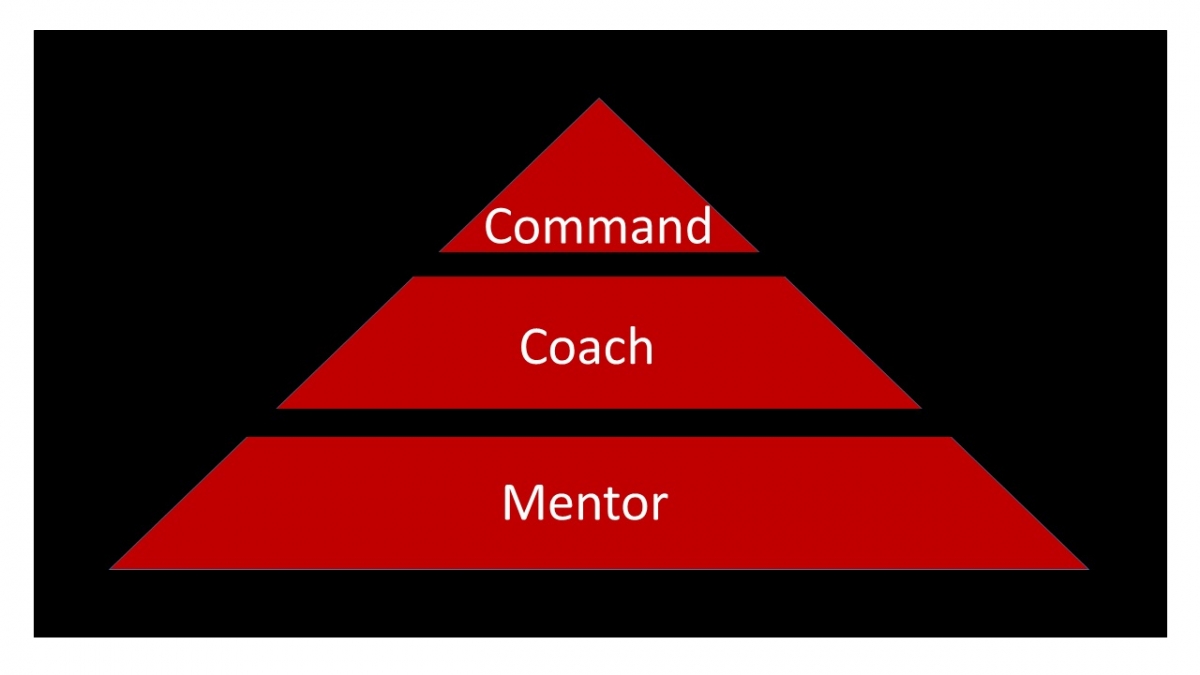

We visualize these roles as a pyramid as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: The 3 Roles of a Leader

We visualize these roles as a pyramid for two reasons. One, as a ratio of time, it takes much longer to mentor someone than it does to coach or command them. Coaching, like mentoring, is an ongoing process, but we all have numerous responsibilities in our jobs and there are systemic limitations on how much time we can spend either providing or receiving training. Commanding takes very little time (i.e., “Call Client X.” “Follow the Standard Procedures.”).

Second, the pyramid also represents the structure of an effective organization and how its leaders should spend their time fulfilling their roles. The foundation of any organization is its culture, what it means to be “one of us.” We can coach our teammates on the skills they need to succeed, and we can command them, but if we have not mentored them on what it means to be “one of us”—if they don’t know and then adhere to our culture—in the long run, regardless of talent, our organization will fail. Therefore, especially initially, much more time should be spent mentoring than coaching, and coaching than commanding.

Inverting the Pyramid

As leaders, regardless of the team or the battlefield we compete on, we can invest money and time into our organizations. Unfortunately, few of us have an unlimited amount of money to invest into making our organizations world-class and none of us have an unlimited amount of time to do so. Even if our budgets are small or non-existent, time is our biggest limitation. There are only 24 hours in a day. Most people choose how they want to spend their time. In contrast, the most successful people and leaders choose how they must invest it.

As the leaders of our organizations, every minute of our time spent mentoring and attempting to improve an individual’s behavior on our team is one less minute we can invest in another team member or other mission essential task. Like all investors, we invest most of our time (and money) into those investments we believe will give us the greatest return on our investment.

Most coaches and business leaders invest most of their time improving the behaviors of their highest performers, the individuals who have the greatest talent for that chosen battlefield. We understand and agree with this philosophy. Basic mathematics does, too: In any investment, if we make our top 10 percent 5 percent better, we get a much greater return than if we make our bottom 10 percent 5 percent better.

Unfortunately, very often, the incredible amount of time we invest in improving the behaviors of one of our most talented performers does not return any positive benefit to the team. Our rate of return on that investment is zero! Further, as it relates to time, not only is our rate of return zero, but there has been an opportunity cost for that investment. We could have invested our time elsewhere, specifically in other members of our team. They may not have been our best performers, but our rate of return would have been greater than zero.

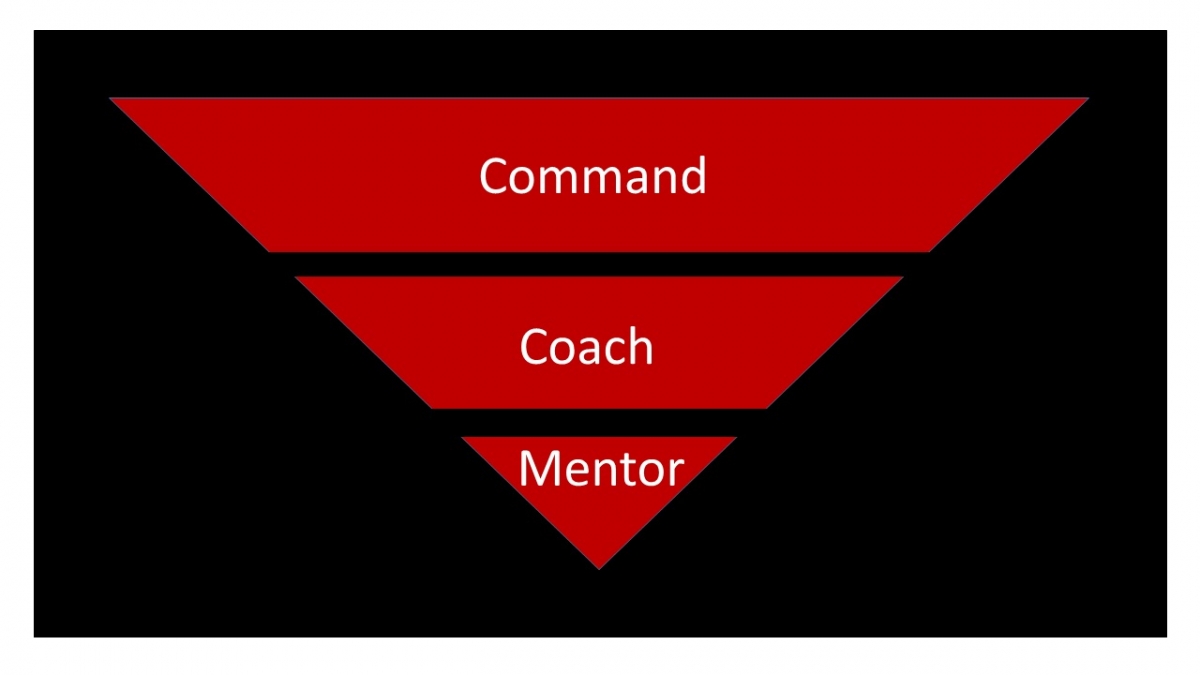

Rather than continue to do that, invert the pyramid.

Figure 2: Inverting the Pyramid

We are still going to command, coach, and mentor that individual, but the amount of time we spend doing each with that individual will change dramatically.

We cannot tell you when to invert the pyramid—that is the “art” of leadership—but whenever a leader finally chooses to do so with a member of the team, his or her common reaction is: “Phew, I just wish I had done it six months ago.”

Many leaders initially will push back on this and ask, “How is this taking care of their teammates?” They will question how “giving up” on a teammate could ever be in their best interest. Our response to that leader is to remind them that leaders take care of their team by making every decision they ever make by thinking about what is in the best interest of the team, not any one individual. And certainly not one who is providing the team with a negative return on the leader’s investment (time).

Further, inverting the pyramid is not “giving up” on a teammate. We are still going to coach him or her to the best of our ability. We will just spend more time commanding that teammate and less time mentoring him or her.

Great leaders consistently accomplish the mission and take care of their team. To do so, they must be able to effectively command, coach, and mentor every member of their team—just not the same amount with every teammate. Remember the Pyramid!

Excerpt from “The Program: Lessons from Elite Military Units for Creating and Sustaining High Performing Leaders and Teams” by Eric Kapitulik. The book is available via TheProgram.org, Amazon, B & N, and other booksellers.

Eric Kapitulik was an Infantry Officer and Special Operations Officer with 1st Force Reconnaissance Company, 1st Marine Division. He received his MBA from the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business in 2005 and founded The Program in 2008. Kapitulik has participated in eight Ironman Triathlons, is an avid mountaineer, and has summited five of the Seven Summits (the highest peaks on each of the seven continents). Learn more at TheProgam.org and connect with Eric via Twitter + Linkedin.