Given that trainers are in the education business, how “educated” are we about one of our most significant purchases: technologies for learning? In the March/April 2015 issue of Training, we reported on trainers’ readiness to purchase a variety of learning technologies based on a survey of 300-plus training professionals (“How Much Do You Know About Learning Technologies?” http://trainingmag.com/trgmagarticle/ how-much-do-you-know-about-learning-technologies).

In this issue, we report the rest of the study results, which look at how trainers prepare for, and participate in, the purchasing process. This includes the extent of purchasing authority participants have, how they conduct research and prepare for technology purchases (including the process of interviewing prospective vendors), what happens after the sale, and the extent of trust they have in vendors.

Training professionals working in organizations that purchase technology might use these results to benchmark their internal processes for researching and purchasing technology. Readers working for organizations selling learning technologies and related services might use these results to gain new insights into their customers.

GENERAL COMFORT WITH PURCHASING

We reported in the last issue that comfort levels for purchasing particular types of learning technologies vary, from generally high levels of confidence for purchasing tools for creating e- and m-learning programs and moderate to low levels of confidence for purchasing enterprise technologies, such as learning management systems and content management systems.

Overall, however, participants generally report strong levels of confidence in purchasing learning technology. More than half report feeling generally comfortable with assignments that involve the purchase of learning technology. Experience either in the field, with prior purchases, or in technical jobs is a primary reason many feel comfortable with purchasing learning technology. One respondent commented, “I have worked in this area for 18 years, so I know the tools available. More importantly, I have learned to facilitate conversations so the focus of purchasing the tool meets the organization’s needs and is not just a fancy tool with bells and whistles.”

Other reasons for feeling comfortable with purchasing learning technology include: research skills (comfort with learning what’s needed to make an effective purchase); strong internal purchasing processes that provide guidance with research and selection; past purchasing experience, and a sensitivity to the needs of users of learning technologies.

But 30.5 percent of respondents report feeling neither comfortable nor uncomfortable with purchasing learning technology, and a small group, 11.9 percent, feels uncomfortable. In most instances, the discomfort stems from a lack of prior experience and a lack of knowledge and skills. Some participants say they feel overwhelmed by the number and types of products available and fear the moving target of technology (a good choice today could be outdated six months from now). In addition, some participants feel u n comfortable purchasing technology because they believe they lack a voice in the process: Even if they offer suggestions or raise concerns, some participants fear no one listens to them.

WHO AUTHORIZES PURCHASES?

As noted in the previous article, most Training and Development professionals play an advisory role in purchasing learning technologies, either serving as the primary advisor to the decision-maker or offering suggestions. But who actually serves as the decision-maker? The answer to that question has two components:

1. Which function “owns” the decision: Information Technology/Information Systems (IT/IS) or Training and Development?

2. Which executive signs off on the decision?

The significance of which function “owns” the decision is important. On a professional level, one of the key responsibilities is decision-making authority over the processes and tools used to perform work. On a practical level, choices made by IT/IS often are received poorly by Training; the opposite is also true.

In nearly half of the organizations (48 percent), “ownership” of the final choice of learning technologies varies, depending on the purchase. Training approves some; IT/IS approves others. In approximately one-third of organizations, Training and Development makes the decision with input from IT/IS. In another 11.8 percent of organizations, the Training and Development group makes its own decision. Only in 10.5 percent of organizations does the IT/IS group make the final decision with input from Training and Development. In other words, most Training groups have much authority over choosing their own tools.

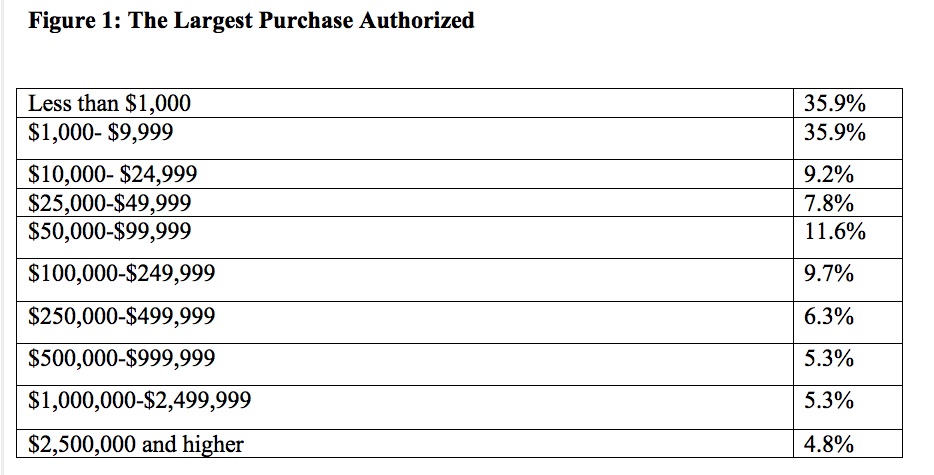

Most of the participants in this study lack the authority to purchase anything other than e- and m-learning authoring tools. The majority (71.8 percent) of participants have only authorized purchases of less than $10,000. In fact, just over a third (35.9 percent) have only authorized purchases of $999 or less. These authorization levels are more than sufficient for most authoring tools but not sufficient for most enterprise learning software. Note, however, that 31.4 percent of participants have authorized expenses of $100,000 or more, which is more than sufficient for enterprise learning software (see Figure 1).

In most organizations, a senior executive approves the expenditure. In several, it is the leader of the organization, such as the executive director, general manager, or president. In others, it is another member of the C-suite, such as a CIO or COO. And in others, approval might come from a contracting or purchasing office. The next most frequently cited approval source is Training management. A few organizations use a committee system, and the committee approves the final decision.

CONDUCTING RESEARCH AND PREPARING FOR PURCHASES

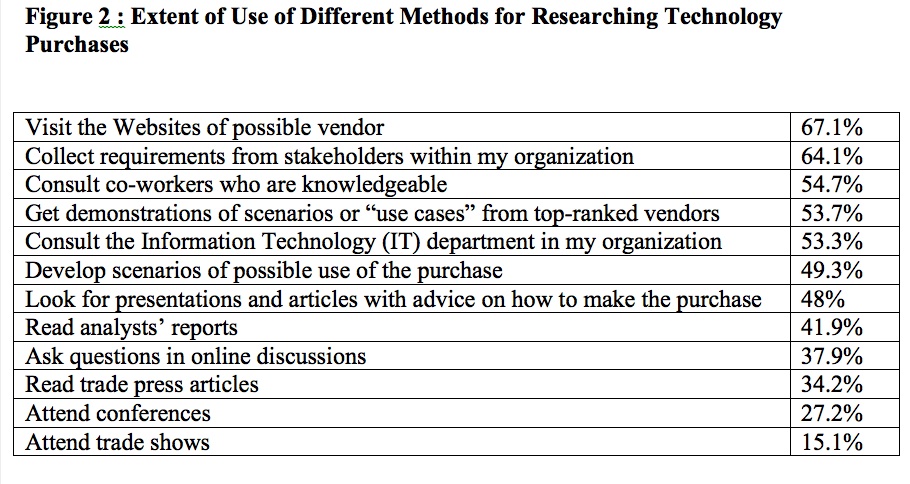

The research process includes two phases: conducting background research about products and needs, followed by a series of meetings with prospective vendors to choose products. Given this breadth of activities, participants use a variety of means to conduct research for a purchase (see Figure 2).

Some practices for researching purchases are used by half or more of the participants. These include:

- Visiting the Websites of possible vendors

- Collecting requirements from stakeholders

- Consulting knowledgeable co-workers

- Getting demonstrations of scenarios or “use cases” from top-ranked vendors

- Consulting the IT/IS department

- Developing scenarios of possible use of the purchase Some practices for researching purchases are used by roughly one-third of the study participants. These include:

- Looking for presentations and articles with advice on how to make the purchase

- Reading analysts’ reports

- Asking questions in online discussions

- Reading trade press articles

Approximately one-quarter of participants researched purchases by attending conferences and trade shows. Additional research methods include consulting a network of peers (other trainers, knowledgeable outsiders, forming committees) for advice; asking for trial versions; and starting the process with a Google search.

AFTER THE SALE

An important part of the sales process is after-sale support. Two of the issues most important to customers are availability of the vendor to answer questions and the availability and effectiveness of training.

In terms of availability to answer questions and provide support after a purchase, only a third (33.3 percent) of respondents feel that vendors are available to do so and are responsive to requests. A larger percentage of participants (39.8 percent) feel that vendors are available to support some products but not others. Some participants (10.9 percent) find that vendors are only available if the customer pays. In a small percentage of cases, respondents feel vendors are only available if pressed or not at all (2.5 percent in both cases).

In terms of follow-up training for recently purchased technology, most participants take it. Although a small number of organizations only make that training available to technical staff (12.7 percent), most make it available either to their technical staff and lead users (34.3 percent) or all users (14.2 percent). Many participants, however, are either unaware of training (15.2 percent), not sure about available training (15.2 percent), or say their vendors do not offer training (8.3 percent).

Most of those who take the training (75.9 percent) feel comfortable using the products after training. Several participants commented that training familiarizes them with the products, but proficiency comes with use. As one participant advised, “Triage the information… categorizing immediate needs, later needs, and nice-to-knows. This ensures that the primary and secondary tasks/responsibilities that have to be taken care of are addressed, while collecting a broad understanding of what we might be able to do with the technology . . .three to six months down the line.”

A few concerns cause participants to feel training is generally not effective. One concern is that training focuses on “how to use features, which I could figure out on my own, and not a strategic training of how to use it to meet our needs.” Another advised vendor trainers to “help the buyer see the big picture and how the technology applies to them.” Another concern is training conducted by “salespeople” rather than “tech developers and programmers” who can explain “the back end to the technology.”

TRUST FACTOR

One of the challenges facing both trainers and their vendors is trust. Only 14.4 percent of participants trust both the prices and descriptions of the products and services offered. In contrast, nearly twice as many participants—27.9 percent— trust neither the statement of price nor the description of products. Another 19.4 percent trust descriptions of products, but not prices, and 14.4 percent trust the prices but not the product descriptions.

Several issues drive the low level of trust. One is pricing, which many participants characterize as “flexible.” Several commented that some vendors have a low base price and require “add-ons that drive the price up.” Participants added that initial quotes often omit the add-ons, driving up the final price quote after a decision is made. Others feel that vendors have different prices for different organizations and that their class of organization receives the higher price.

Another issue driving the low level of trust is being sold a product that does not meet the organization’s needs. “I believe many companies will prioritize making a sale over being honest about whether their product is a good fit,” one participant commented. “Or they are unfamiliar with our industry and not able to understand our needs.”

Perhaps the most serious trust-breaker is a bad experience with a vendor or hearing about one from a colleague. Although some participants take a case-by-case approach to vendors, others transferred one or two bad experiences to all vendors.

CONCLUSIONS

The survey results suggest that, overall, trainers are generally well prepared to effectively purchase learning technologies. Preparation is strongest for purchasing tools for creating e- and m-learning. Preparation for learning and talent management systems also seems strong. Preparation for course management systems, learning content management systems, and content management systems, however, is weak.

Another issue affecting the purchasing process is the lack of use of third-party, independent information in the purchasing process, such as analyst reports, trade press, and conferences and trade shows. The third issue is the low level of trust between trainers and their vendors. The study suggests some of the issues that fuel it—these should be considered when trying to bridge the trust gap.

Survey Methodology

Several e-mail messages were sent to members of the Training magazine community to invite their participation in the study during a five-week period between November and early December 2014.

To reflect the needs of different stakeholders, we offered three versions of the survey: one for training practitioners and managers, one for vendors (who sell the technologies and related services), and one for full-time instructors and researchers.

We received 526 responses, of which 322 were usable: 11 from academics, 17 from vendors, and the rest from training practitioners and managers. The responses reported here are from the third and largest group.

About the Study Participants

The survey participants range in age from under 22 to more than 66. In general, participants skew a bit older, with largest groups between 36 and 45 (19.2 percent), 46 and 55 (37.4 percent), and 56 and 65 (22.7 percent). All but 6 percent of participants have completed some post-secondary education, with more than half (56.6 percent) holding Master’s degrees.

Approximately a quarter—25.8 percent—hold degrees in educational or instructional technology and another 8.7 percent held degrees in a technology field.

In terms of job roles, more than a third of participants (34.8 percent) are instructional designers; 8.9 percent are instructors; 17.2 percent are training managers; 20 percent middle managers; and 8.9 percent are senior executives.

The majority of participants are employed by organizations working in fields other than training (71.2 percent), and another 22.7 percent work as contractors or for firms providing training-related services.

About half—50.3 percent— report to HR and another third report to Operations. People working in all industries participated and none dominated the results. The top five industries represented just below half the participants: government and military (13.6 percent); health and medical services (11.6 percent), higher education (9.6 percent), and finance/banking and technology (7 percent each).

Most participants (78.3 percent) work in the U.S., while 16.7 percent work in Canada.

Saul Carliner, Ph.D., CTDP, is Research director for Lakewood Media and an associate professor of Educational Technology and Provost’s Fellow for Digital Learning at Concordia University in Montreal.

David W. Price is a Ph.D. student in Education, with a focus on educational technology, at Concordia University.