For years as a manager, I hated organizational politics. I was a “naïve rationalist” who believed that the best ideas with the best arguments naturally would come to the surface and rule the day. How wrong I was! I refused to get my hands dirty and engage in petty politics; if they couldn’t see the brilliance of my ideas, that was their loss. How self-righteous it made me feel.

The reality is that organizations are inherently political, given the fact that they contain a variety of power relationships, competing interests and needs, and finite resources. Just because organizations are becoming flatter and increasingly borderless doesn’t mean politics are dead or dying. In fact, one consequence of reduced hierarchy may be the need for a broader distribution of political competence.

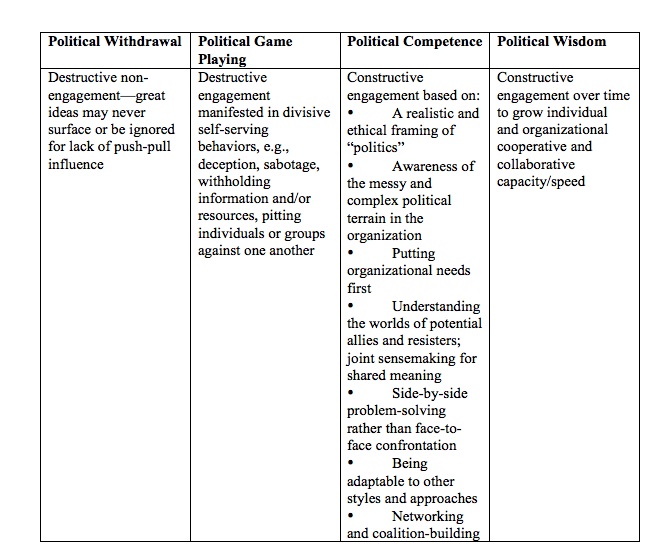

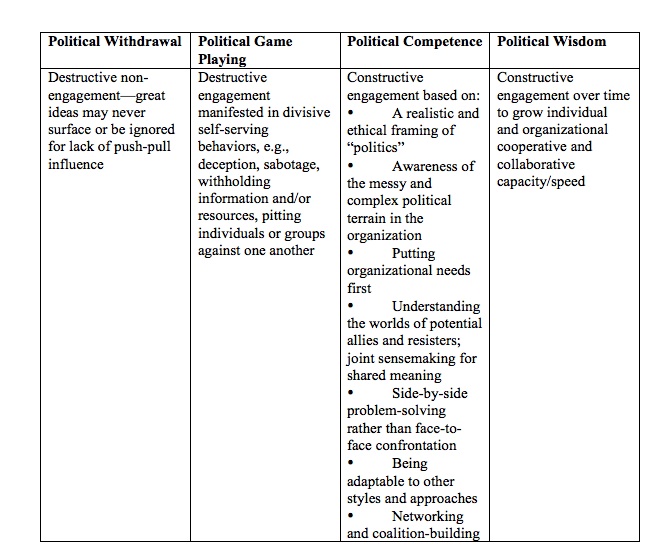

Part of the problem is that “politics” have been hijacked by the dark angels of our existence. We quickly associate the term with corruption, backroom wheeling and dealing, scheming and double-crossing, self-serving lying and manipulation, bullying, and power plays. If organizations are inherently political, we cannot allow this cynical mindset to dominate the political cultures of our organizations. Let me distinguish between what I’ll call four political states. Two are constructive and two destructive.

Consistently applied political competence is critical to individual success, and to the emergence of a healthy and productive political culture in the organization—a culture that recognizes political realities but is intolerant of destructive engagement. Political competence is a large topic, and I’ll try to cover more in later articles; for the moment, let me highlight two important components:

Adopt a realistic and ethical framing of “politics.”

Joel R. Deluca in his book, “Political Savvy” (EBG Publications, 1999) defines “political savvy” (a term sometimes used instead of political competence) as “ethically building a critical mass of support for an idea you care about.” When framed in that way, “politics” is a term I can live with and an activity I can constructively engage in. If we only see politics as a dirty game of scheming and calculating for gaining power, many of us are much less likely to champion ideas we feel are important. Politics are neither good nor bad (although there can be bad politics); they are simply a reality when people live and work together in groups.

Sometimes we use the phrase, “influencing without authority,” but we still need to exercise political competence and build a politically healthy culture when we have authority. “Influencing without authority” may help us feel that we are being non-political, but that is not so. If we substitute “influencing” for “politics,” that doesn’t necessarily eliminate the dark side, although it might make us feel better about ourselves and less cynical. The bottom line is that there are many people in organizations with honesty and integrity who simply want to get things done to benefit the organization; those people must become politically competent and establish political wisdom in the wider culture

Engage in reciprocal networking and coalition building.

Some people see networking as simply self-serving and inauthentic—that you are looking to exploit others for your own gain. In my experience, exploitative people quickly are found out and dropped. Good networks are reciprocal; they are rich in give, as well as take.

Unless you network, how will you find others who share and support the ideas you care about or those who can enrich your perspective? One of the problems in complex organizations is what Max Bazerman and Dolly Chugh call “bounded awareness”— “…cognitive blinders [that] prevent a person from seeing, seeking, using, or sharing highly relevant, easily accessible, and readily perceivable information” (Harvard Business Review, January 2006). We cannot be politically competent with a restricted awareness. How can we hope to influence and build support if we are blind to the likely impacts of our ideas on others? The quality and diversity of our networks reduces the risks of bounded awareness.

In flatter, borderless organizations, a critical mass of support matters. Trying to go it alone is likely to be the death of an idea or the implementation of a bad idea. Networks can coalesce into purposeful coalitions that concentrate and direct energies for the changes we desire.

My days as a naïve rationalist are over. Trying to stand above politics does no one any favors, but we have to define organizational politics on our own terms, not on how others have defined it for us.

Terence Brake is the director of Learning & Innovation, TMA World (http://www.tmaworld.com/training-solutions/), which provides blended learning solutions for developing talent with borderless working capabilities. Brake specializes in the globalization process and organizational design, cross-cultural management, global leadership, transnational teamwork, and the borderless workplace. He has designed, developed, and delivered training programmes for numerous Fortune 500 clients in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Brake is the author of six books on international management, including “Where in the World Is My Team?” (Wiley, 2009) and e-book “The Borderless Workplace.”