In the following scene from “Lead With Respect,” a business novel about why developing people’s abilities as problem solvers is the ultimate sign of workplace respect and a decisive business advantage, Jane Delaney, CEO of struggling software company Southcape, is angry.

She is talking to Mike Wembly, the company’s chief technologist, who is about to hold the first session of what he is calling “Southcape University,” his new internal training effort focused on building problem-solving skills. This is the first time Delaney is hearing about it from Wembly. In what follows, Wembly gives an impromptu preview of the training to the boss…

By the time they reached the office, Jane couldn’t contain herself any longer.

“Look, Mike, you know how I hate surprises. Let’s go to my office and preview what you’ve cooked up for Friday.”

She was surprised to hear that he’d looked up lean management and problem solving and discovered a full methodology. He then made the astonishing step of going to a training session—himself, Mike, the famous pundit and knower of all things.

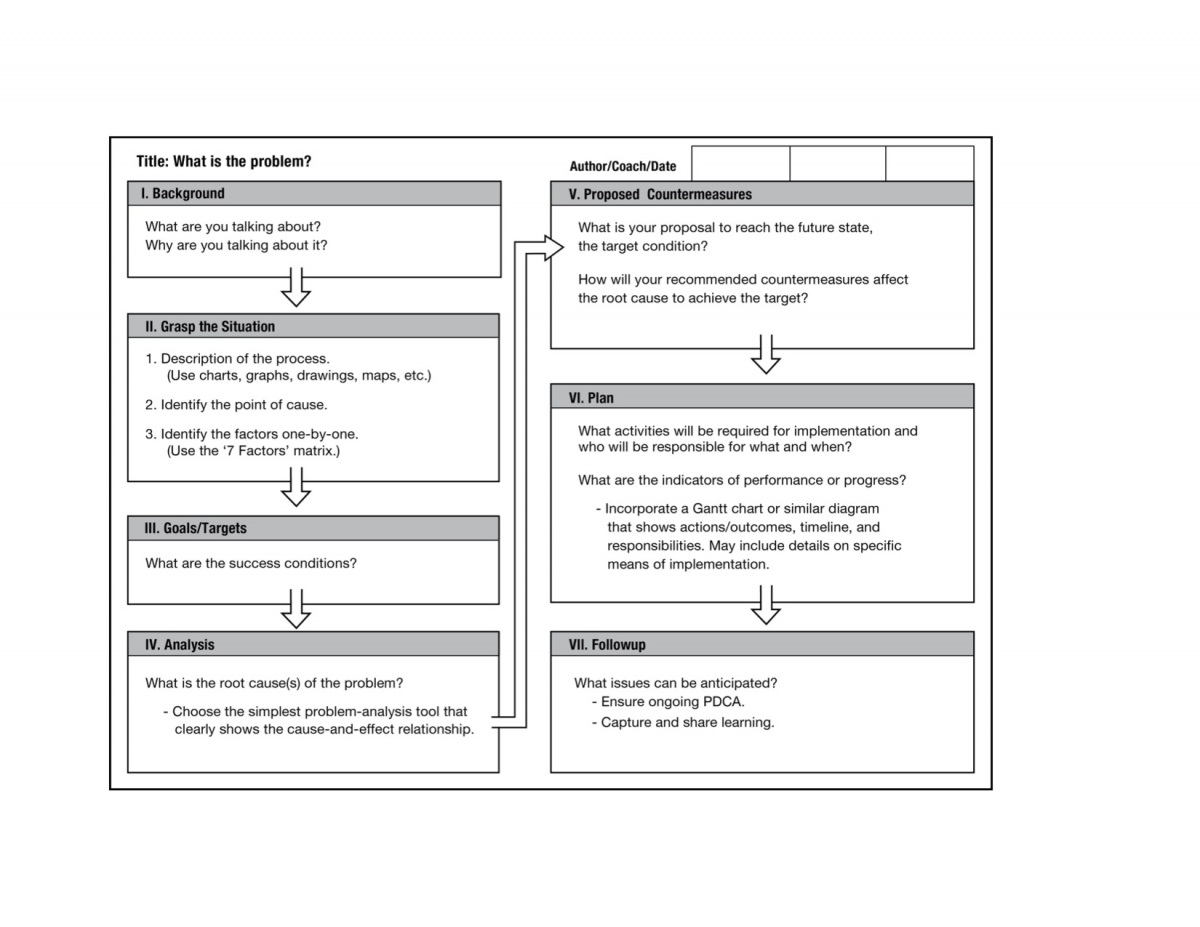

“It’s a method of problem solving called an A3,” he explained excitedly. “The idea is that a full problem-solving story should fit onto an A3 piece of paper.”

“A3, as in the paper size?” Jane asked.

“Yes, the paper you find in the copy machine. It’s the largest piece of paper we have around the office.” He rummaged around her office as if it were his own, found a large sheet of paper with writing on the front, turned it over, and began sketching on the back.

“First, clarify the problem. You need to visualize the gap between what’s actually happening and the ideal situation. The idea is to find the measure that best represents the problem, and show historically and graphically where you are and where you want to be. If we can’t do that, we don’t understand the problem well enough to solve it.

“Second, break down the problem. This is about drawing out the process generating the situation we’re looking at, identifying exactly where things go wrong, and listing potential factors. You’re supposed to test every factor to confirm which one has the greatest impact on the problem.

“Third, set a target. Once you’ve figured out the factor having the biggest impact on performance, you can set a performance target, aim for total eradication of this factor, and guesstimate what impact it would have on the indicator. This also gives you a due date.

“Fourth, seek root cause. Why is the main factor occurring? You ask why repeatedly until you find a cause that is so large that it’s outside your immediate action range. The idea is to find the most fundamental thing that we can affect rapidly, and focus on it.

“Fifth, develop a number of countermeasures. If you can only come up with one solution, you haven’t understood the problem fully—or you’re jumping to the one solution you’re comfortable with, which may be second best. You need to force yourself to explore different routes to address the root cause and then pick the one that’s going to follow through on the basis of impact and cost.

“Six, follow through. Plan the implementation of your countermeasures and make sure all happens on plan. If something gets off track, you need to see this early and ask why? Maybe you’ve missed something, or maybe the commitment to solve the problem is lagging.

“Seven, check the results and the process. Are you getting the expected results? Have you done what you planned to do? I guess that’s what you’d call confirmation.

“Eight, adjust or standardize. How do you make sure these results will hold? What else do you need to fix to make sure the new process will be sustained? What issues remain open? And does what you’ve learned apply elsewhere?

“And it all fits on an A3 sheet of paper, to formalize learning and communicate it easily.”

The A3 Problem Solving Sheet

“On one single sheet? How does that help?” Jane asked.

“That’s the brilliance of it!” he laughed, having his fun. “It’s a great communication tool. Look on top here, besides the title, we have several boxes,” he explained as he drew. “They’re for sign-offs by the A3 author and coach, and the date. The point of these A3 sheets is not the problem-solving structure, it’s the fact that the sheet supports a structured problem-solving conversation between two people.”

“Um …”

“Say I coach you—heaven forbid—on how to use the cloud to store your personal data.”

She raised an eyebrow and gave him her best forbidding stare.

“First, we would have to agree on a problem title, which is far harder than you’d think. Then we have to agree on the problem definition—what is the gap to standard? This means agreeing on what is the standard, ideal, etc., what is the current situation, and how we’re going to measure this. No mean thing!

“Then, we have to agree on what are the most influential factors, how we tested each of them, and how we’ve confirmed our hunches.

Then we have to agree on a meaningful target. Too low and there’s no challenge to look for breakthrough ideas; too high and it’s unrealistic.

Then we have to agree on what we consider the root cause.

“Then we have to agree on what alternative actions we can think up, and which one we’ll choose to have a go at. Then we have to put a plan together and get it done. Then we have to agree on what impact our efforts have had and what effects we can see. Then we have to agree on what conclusions to draw from the entire exercise.

“It may sound formal, and perhaps mechanical, until you try it and discover the intuitive aspect and power of the process. I see it as a great platform for innovation—a way to develop basic skills that enable the individuals to learn and develop mastery—like a musician doing scales and exercises. The beauty of the A3 is that while an author is using it to explore and learn on their own, as the coach, I can steer them through the process, challenge their assumptions, and open up unseen options.”

“It does sound impressive,” Jane agreed cautiously.

“The elegance of it is that this one-page document should read as a simple story that can be shared more widely with other stakeholders to see whether they agree on the thinking, or whether we’re missing something big.”

“And you’ve completed some of these A3s?”

“The proof is in the pudding. Daniela Webb is presenting hers tomorrow, we’ll see how that goes.”

Excerpt from “Lead With Respect: A Novel of Lean Practice” by Freddy Ballé and Michael Ballé (Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc.: August 2014). For more information, visit http://www.lean.org/Bookstore/ProductDetails.cfm?SelectedProductId=386 or contact LEI Communications Director Chet Marchwinski at cmarchwinski@lean.org or (m) 203.470.7377

Michael Ballé, Ph.D., is a business writer, columnist, and executive coach who has studied lean management transformations for the last 20 years. He is associate researcher at Télécom ParisTech’s Projet Lean Enterprise and co-founder of the French Lean Institute. He coaches senior executives in using lean to radically improve their businesses’ performance and establish lean culture. Together, with his father, Freddy Ballé, he also has co-authored the business novels, “The Gold Mine” and “The Lean Manager.”

Freddy Ballé started visiting Toyota plants in Japan in the mid-1970s while head of product planning and later manufacturing engineering at Renault, where he worked for 30 years. Upon leaving Renault, he pioneered the full lean system implementation at Valeo as Technical vice president, then at Sommer-Allibert as CEO, and later at Faurecia as Technical vice president.