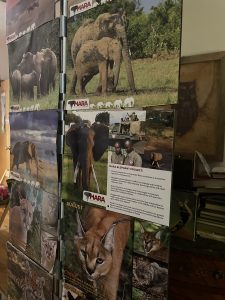

When a glass panel on my standalone closet fell out, scattering dangerous shards across my apartment floor, I didn’t buy a new closet. I carefully cleaned up the mess and used Gorilla Tape to secure the remaining glass panels. Then, about a year after that, I tore out the pages of calendars with photos of big cats and elephants and taped those photos over the Gorilla Tape. It’s not that I don’t want a new closet; it’s that the expense and difficulty of getting one for now isn’t worth it to me.

There are many people who would not have been able to live with my admittedly unorthodox solution. I saw charm in decorating the imperfections with photos that make me happy. To many others, the only charm would be in having a fully intact, polished glass closet.

In the workplace, how does my personality get along with that of the person who can’t live with a patched-up feature in their home? I have found perfectionism to be a difficult workplace personality. However, when perfectionism is tempered by an understanding that everyone else is not a perfectionist, it can serve a purpose.

“While working toward improvement—and even perfection—in the workplace is by no means inherently negative, more and more researchers are beginning to uncover the ‘dark side’ of perfectionism, and the harm it can do to an individual if they are not careful. Some are calling this kind of perfectionism ‘negative perfectionism,’ ‘maladaptive perfectionism,’ or even ‘neurotic perfectionism,’” Wendy Boring-Bray, DBH, LPCC, wrote in a July 2020 article in Psychology Today.

A doctor who contributed an article to the healthcare trade publication where I am editor went so far as to say she considers perfectionism a red flag in pre-hiring personality assessments. She notes that, along with the trait of dishonesty, perfectionism is not a good fit for her office.

The question is how to take the positive elements of perfectionism and limit the damage it can inflict. I love perfectionist personalities when the person is a perfectionist about their own work, but not the work of others. In that ideal scenario, a high-performing employee always does a flawless job in their own work, and always perfectly meets their obligations to colleagues. But they do not expect co-workers to conform to their perfectionism. When they notice something that bothers them about another employee’s work, they offer to jump in to help, or are proactive and fix what they see as flaws on their own. The problem occurs when perfectionists decide to scour the work of everyone in the office for flaws, and then, rather than fixing things themselves, alert colleagues and the supervisor of the flaws and ask for the flaws to be corrected (by someone else). “It’s not my job,” they whine when a colleague says, “Great, go take care of that.”

An additional problem occurs when the perfectionist is a manager who can accurately claim that fixing the problem is not their job, but doesn’t know how to fix the problem, even if they wanted to. I have experienced managers who both refuse, on principle, to help with anything that isn’t strictly part of their job description, and don’t know how to do almost anything anyway. Is a perfectionist who is not able to pitch in to correct detected flaws a good fit to be a manager? It doesn’t sound like it to me.

Boring-Bray writes that studies have been conducted to find ways of limiting the damage of perfectionists in the workplace. She suggests in the article that many perfectionists are people more prone to neuroticism, anxiety, and depression. Helping a perfectionist continue to do great work while not making the work lives of others miserable is essential.

“One study by Beheshtifar, Mazrae-Sefidi, and Nekoie Moghadam (2011) presented a framework for managing negative perfectionism as it presents itself in the workplace. Within this framework, there was a list of action steps that could be taken to combat perfectionistic behavior, including ideas such as ‘setting SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound) goals,’ ‘confronting the fear of failure,’ and ‘celebrating wins’ (Beheshtifar, Mazrae-Sefidi, and Nekoie Moghadam, 2011). Keeping action steps like this in mind could be an excellent way for organizations to prevent and reduce the effects of negative perfectionism, both on an individual and a systemic level,” Boring-Bray points out.

If I owned a business with a high-performing perfectionist employee who, in addition to doing spectacular work, was making their colleagues’ lives miserable, I would have a conversation to set expectations and boundaries:

“Sarah, your work is wonderful. You’re a standout employee who delivers consistently high-quality work. Those are all positive things. However, as you’re probably aware, you’re a perfectionist and most of your colleagues are not. Our resources are limited, so while it’s helpful for you to point out areas of needed improvement, I would prefer that you point those areas out just to me, rather than directly to your colleagues. I then will decide which improvements need to be acted on and are a priority. Our resources are limited, so if you are not able and willing to make the needed changes yourself, those changes may not be done for a while, or at all. I need to know you can live with that.”

If the perfectionist is too compulsive to live with imperfection outside of their own work, they may not be a good fit for an office with limited resources and a staff that comprises mostly non-perfectionists. It’s OK to acknowledge that a high-performing employee is not a good personality fit for the office, and, as they say at Disney, empower that person “to find their happiness elsewhere.”

Is your corporate culture a good fit for perfectionists? How do you optimize the perfectionist personality while limiting the damage it can do to colleagues?