The subject of leadership has always spawned big questions: What makes a great leader? How does the definition of an effective leader need to change for different organizational levels? What factors need to be considered to identify the right leaders who can successfully transition into higher-level roles, either now or at some point in the future?

Seeking answers to questions such as these, Development Dimensions International (DDI) scientists examined our database of assessment data from 15,000-plus leaders, including more than 300 organizations, 20 industries and 18 countries. This data spanned four leadership levels, including mid-level, operational, strategic executive, and C-suite executive. The resulting report, High-Resolution Leadership (http://www.ddiworld.com/hirezleadership), includes numerous findings about leadership skills and readiness, geographic trends, and the impact of the current and future business context.

In the discussion that follows, we draw on these findings to both illuminate and debunk some commonly held assumptions about what separates great leaders from the rest. We also offer recommendations and specific actions you can take to increase the quality and capability of your organization’s leaders. In doing so, we aim to bring clarity to the complex challenge of predicting stronger leadership.

THE NEED FOR—AND PERILS OF—SPEED

Because business moves at such a torrid pace, organizations find themselves having to thrust leaders into roles of increasing scope and responsibility—ready or not. Predicting who can navigate these transitions is at the very heart of business success. But as the headlines often show, error rates remain high. Accuracy requires an understanding of how leadership patterns (behaviors and personality) differ between higher- and lower-level leaders.

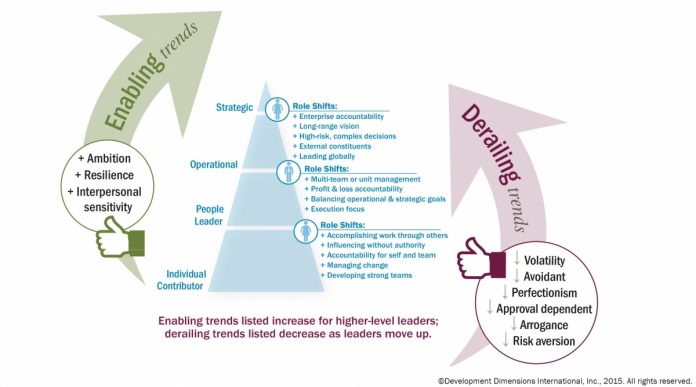

As illustrated in the graphic below, the body of assessment data we examined showed that as leaders progress to higher levels, helpful personality traits such as ambition, resilience, and interpersonal sensitivity trend higher. Also, as leaders move up, the role of derailers—negative personality traits that can undermine a leader’s success, such as volatility, perfectionism, arrogance, and risk aversion—becomes more consequential. This is because more-senior leaders encounter higher-risk, higher-pressure scenarios that can trigger derailing behaviors.

How Personality Patterns Differ Between Higher- and Lower-Level Leaders

From an organizational standpoint, the important point about these personality traits is that they need to be assessed when identifying leadership potential and when making decisions about who to transition to higher-level roles. This is because while all personality characteristics are difficult to develop, derailers are often invisible among lower-level leaders who have not yet experienced the high-stakes environments that so often unleash dysfunctional behavior patterns.

THE EXPERIENCE EFFECT

To varying degrees, a leader’s path to and through the management ranks can be complex, unpredictable, and challenging— but it’s almost always a lengthy path. In our research, average years of management experience range from 12 years for mid-level leader candidates to 18 years for those in C-suite candidate pools. Years of experience often is used as an indicator of leadership strength, based on the assumption that more time being a leader means more skill as a leader.

Because the behavioral assessment database we examined included candidates with varying experience levels, we tested this assumption by asking these questions:

- Does experience actually translate into leader strength?

- How does this vary across leadership skills?

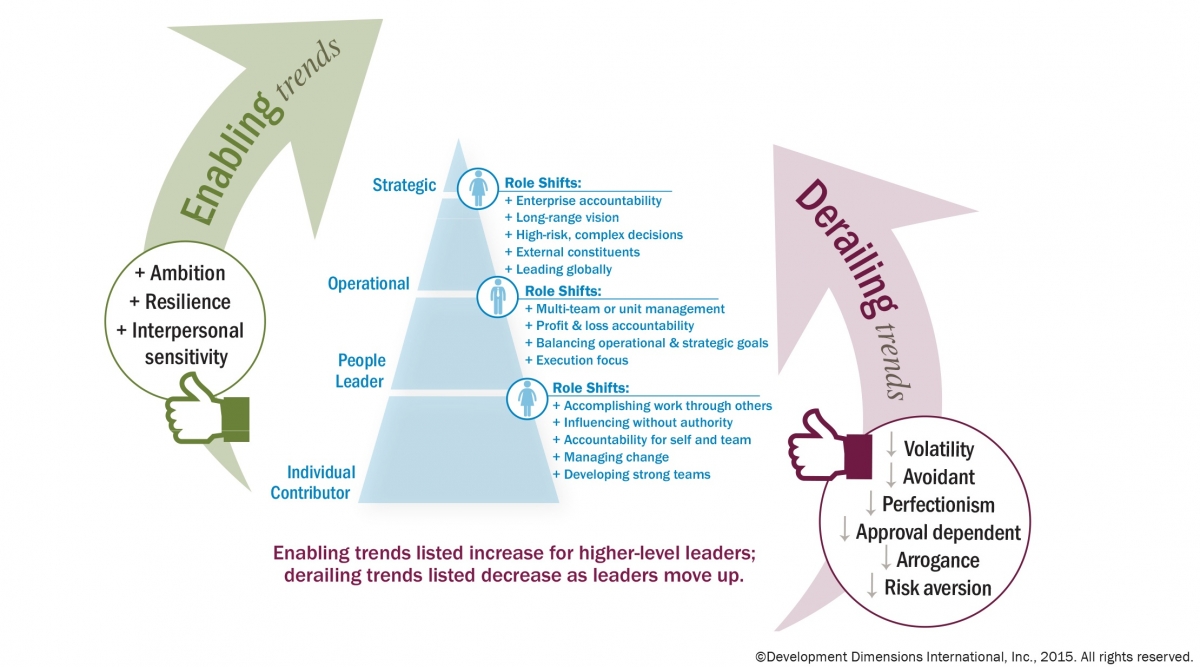

We correlated years of management experience with proficiency in each of 10 key skills. These skills clustered into three types: high growth, moderate growth, and low/ no growth.

- High-growth skills where experience translates into strength: Driving for results, inspiring excellence, and leading teams. These require both goal achievement and team motivation. On average, high-tenure leaders were 4.4 times more likely than low-tenure leaders to be strong in these skills. New leaders struggled most with leading teams, as success becomes increasingly dependent on the capabilities of others versus oneself.

- Moderate-growth skills: Coaching, driving execution, and global acumen. High-tenure leaders were 2.6 times more likely than low-tenure leaders to be strong in this cluster. These skills are developable, but not easily or quickly. Development assignments may be needed to grow in driving execution and global acumen.

- Low- or no-growth skills with virtually no connection between tenure as a manager and strength: Executive disposition, selling the vision, operational decision-making, and customer focus. On average, high-tenure leaders were only 1.7 times more likely than those with low-tenure to be strong in these skills.

WHEN LEADERSHIP PRACTICE MAKES PROFICIENT—IF EVER

We also gauged how many years an average leader needed to exhibit expert-level skill during the behavioral assessment. In the “Skills by Years” graphic below, for each skill, the size of the bubble shows the experience range when most leaders demonstrated mastery, including two that even long-tenured executives rarely perfect: coaching and selling the vision. These skills often must be relearned with each new group of employees and for each new strategy requiring a leader to chart a compelling course.

Recommendations and Actions to Take

-

Realize that experience alone won’t grow your leaders. Practice that is not guided by proper assessment and training does not lead to excellence. On the other hand, we have tremendous evidence showing that, with accurate assessment and the right training, practice dramatically enhances leadership effectiveness.

-

Design high-quality developmental assignments for earlytenure leaders to take advantage of natural growth trajectories for driving for results, inspiring excellence, and leading teams.

-

Align hiring and promotion processes toward low- or no-growth skills. These skills are best targeted through assessment rather than development programs.

- Recognize that some skills, while developable, can be mastered only through sustained focus and extensive support. Two clear examples are coaching and selling the vision, which grow relatively slowly with experience; few leaders ever excel in these skills.

EDUCATION BOTH INFORMS AND MISLEADS ABOUT LEADER SKILLS

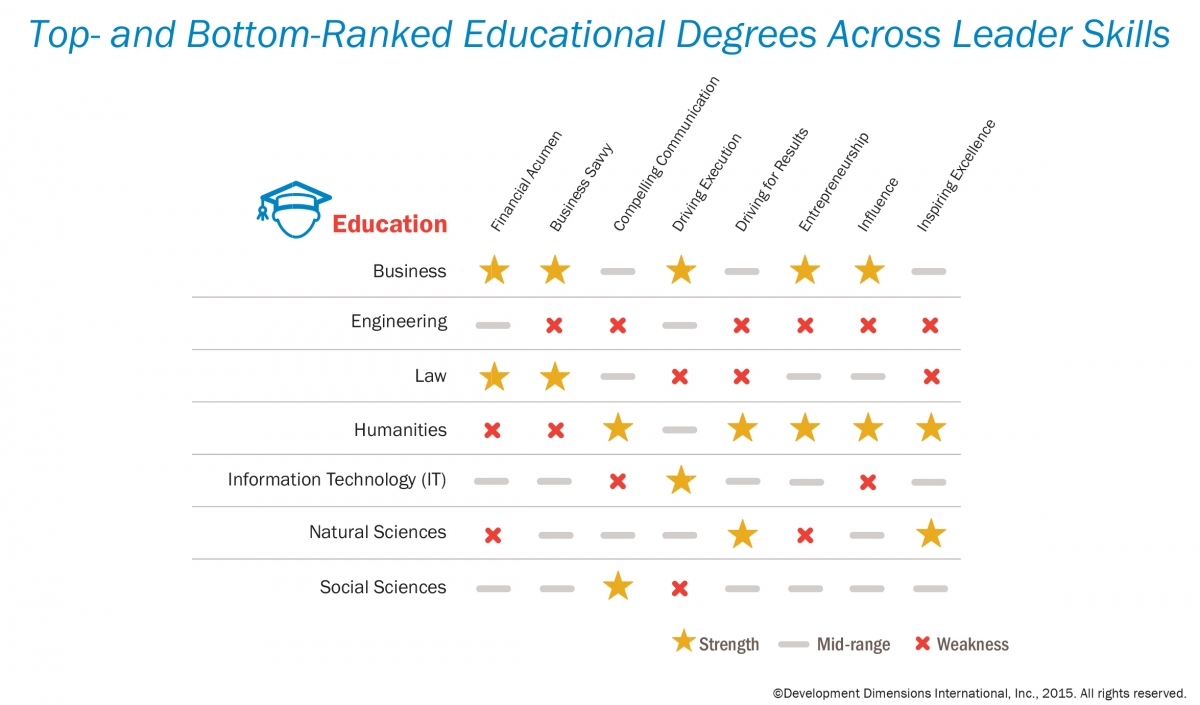

Degrees often are used as proxy variables when reviewing resumes and qualifications, with assumed insight into a leader’s capabilities. Degrees also are closely linked to compensation a decade into one’s career. However, while stereotypes abound about certain degrees (e.g., IT, humanities, MBAs), research on how degrees translate into rigorously assessed leader skills is limited. Our research answers two questions about the educational background of leaders:

- How do skill profiles vary by highest educational degree?

- What skill advantages do MBA graduates exhibit?

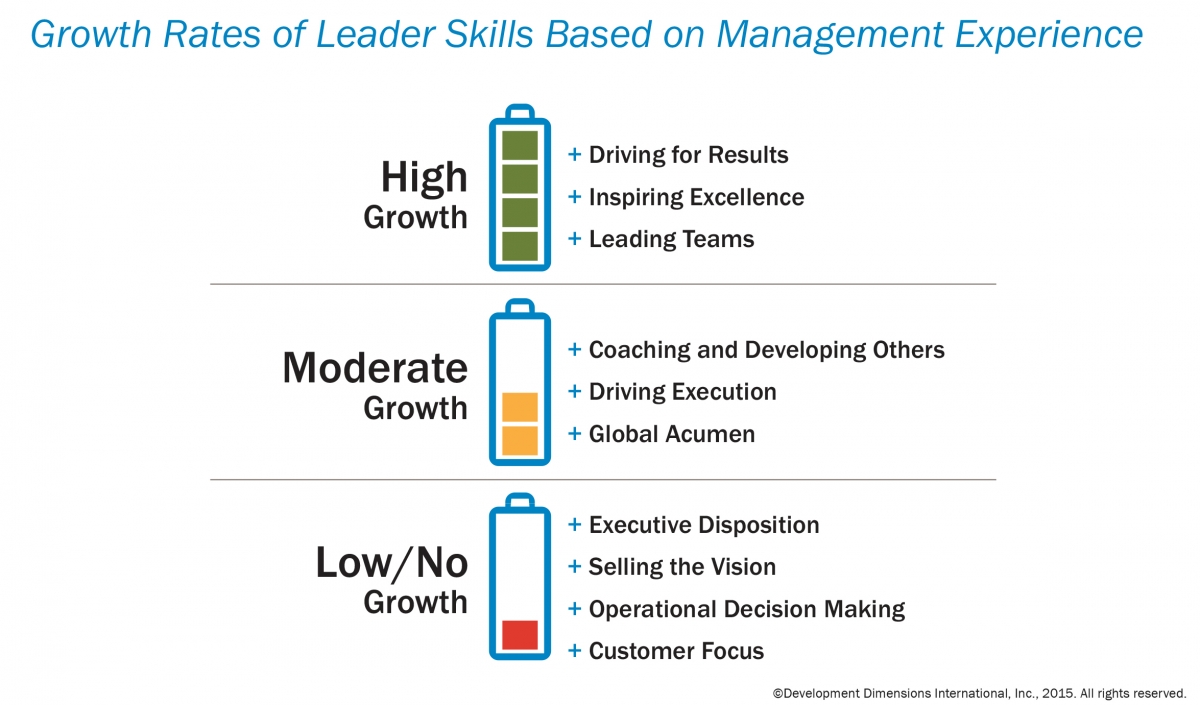

The trends in the “Top-and Bottom-Ranked” graphic below illustrate skill gaps and untapped potential in many degree-holder pools.

Among the largest skill discrepancies are leaders with engineering degrees. As a group, these leaders (often highly technically advanced) tend to face disadvantages in leadership skills. They were near the bottom in proficiency for six of the eight assessed competencies.

Business majors outperformed other degrees on five of eight skill areas. Humanities graduates struggled with business savvy and financial acumen but outperformed other degrees in many skills, and did so through strengths not only in interpersonal competencies (such as influence), but also in results orientation and entrepreneurship. Many humanities programs incorporate debating, communicating, and critical thinking, which would contribute to well-rounded graduates in these fields.

DO MBA INVESTMENTS PAY OFF IN STRONGER SKILLS?

Business was the most common degree across all leaders assessed in our research—but these degree-holders were split between those leaving school after completing their undergraduate business degree (28 percent of those with business degrees), and those who stayed—or returned— to get their MBA (72 percent). The difference in having or not having an MBA degree is extremely consequential for employers—the average starting salary for MBA grads is $100,000, compared to $73,000 for those with business administration Bachelor’s degrees 10 years into their career (a more accurate comparison than new business administration Bachelor’s graduates, since many people return to acquire their MBA after several years of work experience).

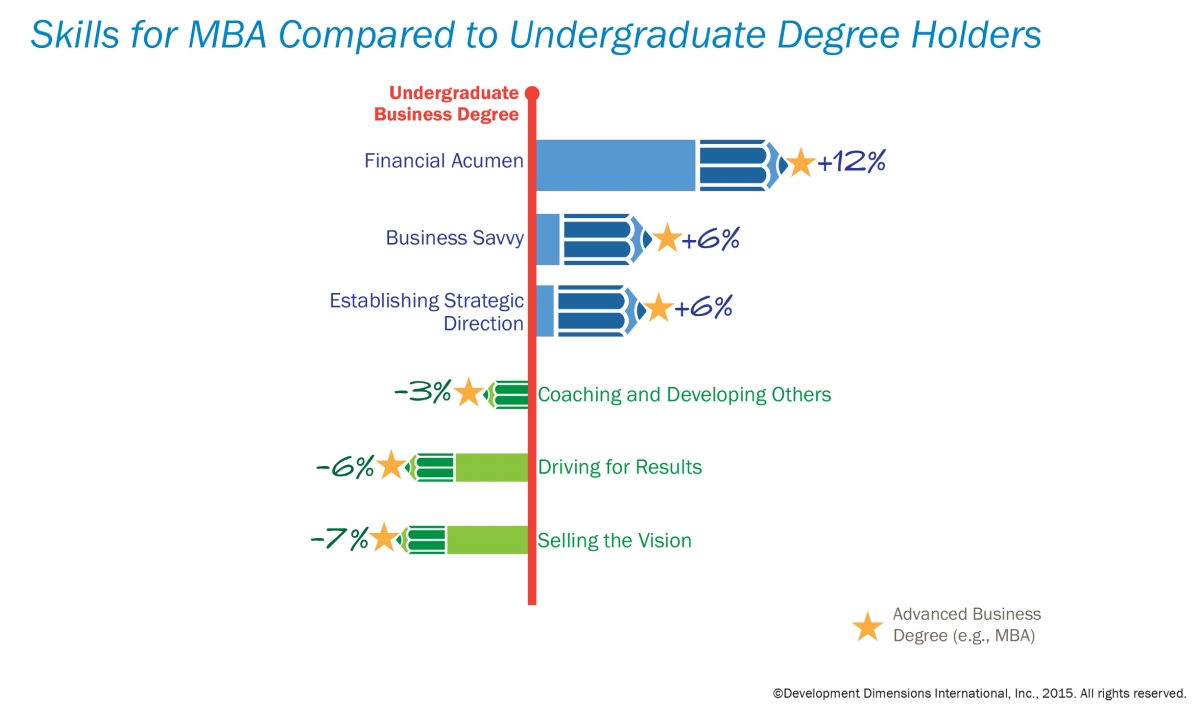

Our research allowed us to see if the higher investment in MBAs is justified by stronger leadership skills. In addition to the analyses above spanning all business degrees, we conducted a follow-up analysis comparing undergraduate and graduate (e.g., MBA) business degree-holders. We found that they diverged on several leader skills. Results are presented in the “Skills for MBA” graphic below.

Our results speak to both the benefits and potential risks of an advanced degree program focused on the management side of the leader’s role. Though management skills were consistently higher for MBA graduates, several other key leader skills show the opposite pattern—coaching and developing others, driving for results, and selling the vision each were notably lower for MBA graduates. Though overall MBA skill profiles are high, this research highlights the importance of considering interpersonal and influence skills alongside traditional “business skills.” Both play key roles in leaders who succeed in not only directing employee performance, but also in inspiring them and encouraging their own development. Perhaps because of these gaps, many educational institutions have begun incorporating diagnostic assessments into their MBA curricula as a gauge of the leadership skill growth from the program.

Recommendations and Actions to Take

-

Challenge—and encourage others to reevaluate—long-held assumptions based on education. Don’t assume education is a proxy for leader development. After all, an Ivy League MBA graduate can still be a horrible leader!

-

Balance the critical technical expertise of associated educational backgrounds with awareness of common skill gaps that, if left unchecked, will curtail their overall effectiveness as leaders.

- Align talent programs to take advantage of the strong management skills of MBA graduates, while remedying any weaknesses (compared to undergraduate business majors) on the interpersonal aspects of leadership.

WHAT SETS SUCCESSION FINALISTS APART?

Succession finalists are a special breed. Most have unique strengths and personality traits that separate them from other leaders. But how, exactly, are they different? The data we examined was gathered from assessments of 243 CEO candidate finalists from 48 organizations. We synthesized this data into a composite profile that allowed us to explore three questions:

- In what areas do top candidates excel?

- How are they wired?

- In what areas do they tend to struggle?

We came away with clear answers. Succession finalists do three things exceedingly well. They:

-

Obsess over execution and results.

-

Instantly and accurately size up complex business situations.

- Fixate on customer needs.

Not coincidentally, these three things also are defining characteristics of highly successful organizations.

As for how they are wired (i.e., their personalities), they are intensely competitive, confident, and emotionally resilient. These top finalists crave attention, suggesting that the top job attracts those who enjoy being noticed for both their talent and their charm. A dichotomy we discovered, however, was that finalists for top roles tend to be creative or pragmatic— but not both. While 21 percent of the CEO candidates in our data set were creative, conceptual strategists, and 29 percent were practical, no-nonsense operators, only 8 percent exhibited a balance of the two.

Of course, like all other leaders, the top succession candidates also have areas in which they struggle. These include a tendency to default to the short term and focus on solving operational dilemmas as opposed to generating effective, long-range growth strategies. When engaging in planning, they tend to treat talent as an afterthought, and they also experience difficulty in being inspirational when it comes to rallying the organization behind their plans.

These strengths, traits, and struggles, of course, don’t define all top candidates, but they do serve to highlight important things that need to be taken into account when evaluating individuals in the running for your organization’s top jobs.

Recommendations and Actions to Take

-

Don’t settle for anything less than deep insight into your top succession candidates. You’ll need accurate data on each candidate’s capabilities to ensure you make the best decisions.

-

Don’t confuse industry experience or business savvy with the ability to think strategically. Great strategists take complex scenarios and chart a clear, manageable path forward that covers all the bases and capitalizes on opportunities. That takes practice, and no small amount of thoughtfulness, smarts, and discipline.

- When building leader development plans for top-level leaders, be specific and zero in on individual growth needs that spark new and better approaches. Even the most experienced leaders need detailed development plans. An effective succession plan pushes senior-level leaders to work toward the CEO’s standards.

GETTING SMARTER ABOUT LEADERSHIP

The findings discussed here were gathered in support of a common purpose: to arm organizations with insights to help them better identify, develop, and deploy their leadership talent—to ensure they have the best leaders at all levels to generate the greatest returns for the business and the organizational culture.

Better intelligence drives better decisions. This fact was reinforced by digging into and sifting through our large body of assessment data. But it also applies to assessment itself.

Assessment is the best way to predict who will succeed in your critical leadership roles. To try to make accurate decisions without this data amounts to flying blind.

Evan Sinar, Ph.D., is Development Dimensions International’s (DDI) chief scientist and director of the Center for Analytics and Behavioral Research (CABER). Sinar consults with global organizations on measurement and analytics of leadership assessment and development programs. He is the lead author of DDI’s High-Resolution Leadership assessment research report.

Matt Paese, Ph.D., is DDI’s vice president of Succession Management & C-Suite Services. He has consulted with CEOs and senior teams from many leading organizations around the world to design and implement strategic talent initiatives ranging from organizational talent strategies through executive teambuilding. He is a co-author of DDI’s High-Resolution Leadership assessment research report and the new book, “Leaders Ready Now,” available in June 2016.

For more information, visit www.ddiworld.com.