For the last 50 years, I have been actively engaged in workforce development as a provider, researcher, consultant, and author. It has been a wild ride since 1968! Now we are at another major tipping point on this journey.

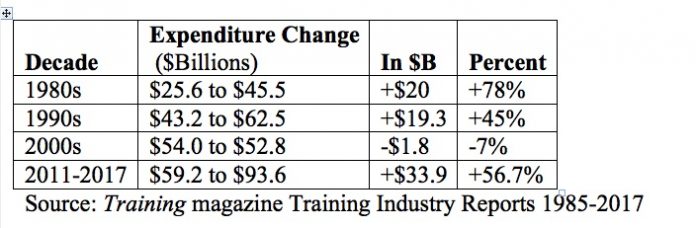

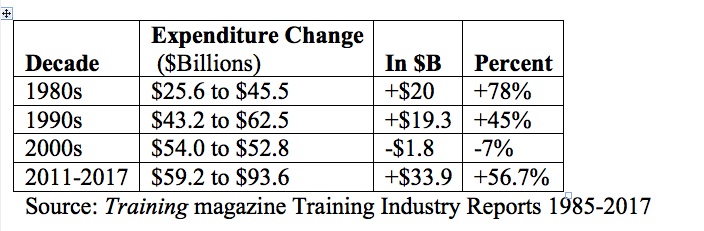

Training magazine’s 2017 Training Industry Report (Training, November/December 2017) showed that U.S. businesses made an unprecedented $23 billion increase in worker training in the last year. Total expenditures rose from $70.6 billion to $93.6 billion or 32.5 percent. This is by far the largest annual increase reported since 1985. Since 2011, business investment in training and development grew by more than 50 percent. (See chart.)

With more than 9 million vacant jobs across the U.S. economy, companies are beginning to radically rethink their investments in worker training and education. The first paragraph of the December 8, 2017, issue of the Kiplinger Letter stated: “Businesses are turning to a new strategy: train the workers they need themselves.”

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce estimates a loss of $26,000 per vacant job in profit or productivity for a business. This represents an overall $234 billion loss to the U.S. economy.

The massive U.S. demographic shift and the increasing educational demands caused by the introduction of advanced technologies across every business sector will continue to energize more business investments in worker training. If this high level of investment is not sustained, it is likely job vacancies may rise from today’s 9 million to 14 million by 2022.

THE BUSINESS CYCLE OF TRAINING AND DEVELOPMENT

Between 1966 and 1988, training and workplace education underwent a fundamental shift. Computer-assisted training, which first was introduced in “learning labs,” became the business response for addressing the need to reskill employees. But during the early 1980s, many organizations began to recognize the limitations of stand-alone computerized training. A human trainer was needed to guide, coach, and motivate individualized learning. Management response to training proposals began to shift away from: “What do you think this business is—a school?” Gradually, larger organizations began establishing Training departments that offered in-house instruction using training designers and professional trainers. During the 1980s, U.S. businesses expanded their training investments by 78 percent to more than $45 billion. (See chart.)

By 1990, the workplace learning revolution was popularized by Peter Senge’s seminal book, “The Fifth Discipline.” American senior management began to embrace investing in their human capital—corporate universities proliferated and “lifelong learning” and the “learning organization” became business buzzwords. By the decade’s end, training expenditures had increased 37 percent to more than $63 billion.

However, by the mid-1990s, a dramatic policy shift gained momentum. Best-seller “Workplace 2000” by Joseph Boyett and Henry Conn advocated shifting the responsibility for employee development back to the individual worker. People were “empowered” to figure out what new knowledge they needed and told to go out and get it. This fit in with an accelerated management focus on short-term financial results. Businesses sought to raise quarterly profits through mergers and acquisitions and aggressive cost cutting, including expanding automation to reduce staff and slashing training budgets. Short-term profit enhancement required eliminating all non-essential business operations. Non-core functions could be outsourced, including Training departments.

As more powerful computer instruction programs appeared, management embraced e-learning because it eliminated training staff and classrooms, and increased employee time on the job. Another appealing feature was that it enabled employees to access learning whenever they wanted it. An added incentive was that e-learning software and hardware could be capitalized as an equipment investment. Over the next 15 years, this business training game plan gained popularity across the U.S. By the end of the first decade of the new millennium, companies had cut their overall expenditures on employee training by 7 percent.

However, research began to appear that questioned the effectiveness of stand-alone e-learning. While it worked well for self-driven, highly motivated, well-educated employees, studies showed that only about 10 percent of the workforce successfully completed pure e-learning programs. Also, it was found to be less useful for training aimed at changing human behavior, such as supervisory or interpersonal skills training, teambuilding, or some types of sales training. Psychological studies indicate that the social component of learning is extremely important for most adult learners. Thus, blended learning gained momentum as it enabled trainees to try out their new skills and obtain coaching from a professional trainer. Ideally, it marries the best e-learning and virtual reality programs with higher-quality classroom training.

Beginning in 2011, the business profit loss generated by accelerating job vacancies has spurred businesses to once again expand employee training and development and cooperate in programs that prepare people with the skills needed in today’s job market. Apprenticeships, “boot camps,” and “earn while you learn” programs are gaining increasing business support.

WHAT’S NEXT

In 2018, we seem to be experiencing a return to a training cycle similar to those of the 1980s or the early phase of the industrial revolution when agricultural workers flooded into the cities from the farms or from overseas as immigrants— a critical need to update the skills of the U.S. workforce. Retraining adult workers and better preparing more of our students for the job market will require an even greater effort than in past eras. Computerization and robotics are disrupting the job market, especially shrinking the demand for manual labor. Some type of post-secondary education and training is increasingly necessary to earn a middle-class wage. Brain power is superseding muscle power.

America’s wealth is built around a knowledge-based economy. Scientific knowledge and technological change are progressing at an ever-increasing pace. Innovation requires utilizing technological advances to produce new goods and services. Lifelong learning is now essential for career success and advancement. A new era of continuous learning has arrived. It will only grow in importance as 21st century workplaces continue to be transformed.

Edward E. Gordon, Ph.D., is president and founder of Imperial Consulting Corporation. He is the author of “Future Jobs: Solving the Employment and Skills Crisis” (Praeger, 2018 new paperback edition) and many other labor studies on the U.S. workforce. Visit www.imperialcorp.com for more information.