This year, the youngest of the Baby Boomer leaders will turn 61, and simple demographics assures that the need to replace the exodus of these aging leaders will accelerate rapidly over the next four to six years.

But are organizations doing enough? Are current leadership development practices setting organizations up for a successful transition?

Studies by McKinsey & Company and J.P. Donlon have found a close correlation between the skills of a company’s leaders and market performance. However, research by Deloitte and the U.S. Federal Reserve show that return on assets (ROA) and productivity growth—both key measures of leadership success—have shown a steady decline since the 1960s. The data does not look good for the strength of our leadership capabilities.

Clearly, effective leadership is critical to success, and development of the next generation of leaders is at a critical stage. Now is the time to take stock of where you are and what you need to do to effectively prepare the next generation of leaders.

ANNUAL LEADERSHIP SURVEY RESULTS

For the second year, Training magazine and Wilson Learning Worldwide teamed up to conduct a survey of more than 500 respondents focused on creating effective leaders and preparing the next generation (see the survey methodology at the end of this article). The results of this survey indicate there is a strong desire and great need to strengthen leadership development efforts. In particular, efforts need to focus on meeting the needs and expectations of the next generation of leaders. This research points to specific actions organizations can take to improve the effectiveness of their leadership development efforts and strengthen their organization’s future.

SHIFTING FOCUS

Based on the survey results from 2018 and 2017, there are some interesting shifts in emphasis.

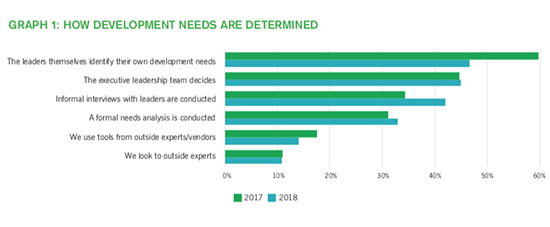

>> DETERMINING DEVELOPMENT PRIORITIES

Results indicate a shift in how organizations determine development needs. As Graph 1 shows, there is a sharp decline in the use of more self-directed methods—leaders identifying their own development needs. In 2017, 60 percent of organizations used this approach; in 2018, only about 47 percent indicated that they let managers identify their own needs. Replacing this approach is the use of interviews with leaders and their managers to determine development needs and a more formal needs analysis process.

>> PRIORITY SKILLS

The skill focus of organizations also shows some interesting changes. Organizations were asked to identify the top five priority skills that are the focus of leadership development efforts. Graph 2 shows the rank order of priority skills for 2018 and the rank order change from 2017. While most of the skill priorities remain roughly the same, there are four notable exceptions. First, Performance Management and Self-Development skills show a marked decrease in priority. Performance Management dropped six slots, from third to ninth, while Self-Development dropped three slots, from 10th to 13th.

In contrast, Motivating Others and Strategy Development show marked increases in priority. Motivating Others increased four slots, from 12th to eighth, while Strategy Development went up three slots, from seventh to fourth.

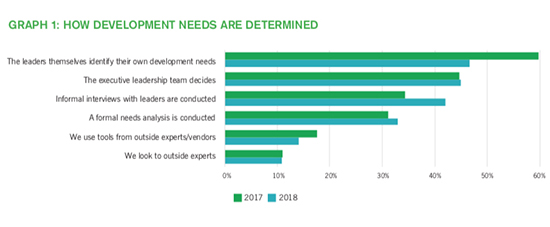

>> LEARNING METHODS

Most of the 24 learning methods used for leadership development did not change meaningfully from 2017 to 2018, with four interesting exceptions. As Graph 3 shows, use of simulations and role-plays shows a marked increase of more than 11 percent, with approximately 82 percent of organizations using simulations in 2018, compared to 71 percent in 2017.

What did simulations replace? Results suggest three methods show the greatest decline in usage: Open-Source Programs (down 7 percent), Learning Portals (down 5 percent), and Gamification Methods (down 4 percent). While not dramatic decreases, this suggests a move away from more learner-selected methods and games for motivation toward the more sophisticated application-focused, game-like activities of simulations and role-plays.

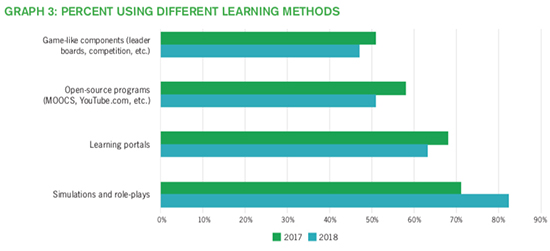

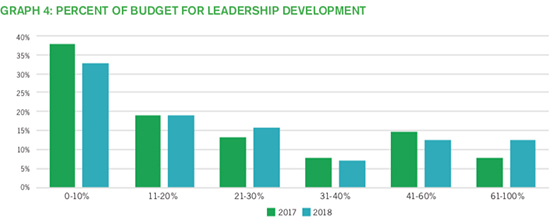

>> INVESTMENT IN LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

There has been only a slight change in how much organizations invest in leadership development. Graph 4 shows an increase in the percentage of the training budget going to leadership development. This means there was a decrease in the number of organizations spending 10 percent or less of their budget and an increase in the number of organizations spending 20 to 30 percent and 60 to 100 percent of their budgets on leadership development. The results also show that the majority of organizations (57 percent) anticipate an increase in leadership development investment, as in 2017.

>> WHO RECEIVES LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT?

One of the most dramatic shifts from 2017 involves who is participating in leadership development programs, as shown in Graph 5. Organizations are directing more of their leadership efforts toward middle managers, supervisors, and high potentials.

Comments indicate organizations are realizing that large numbers of middle managers and supervisors will be retiring soon—and if they don’t begin to prepare the next generation for these roles now, they will have difficulty filling them moving forward.

SUPPORT IN DEVELOPING NEXT-GENERATION LEADERS

Given the need to prepare the next generation of leaders, we decided to explore what is and isn’t working in their development. How seamlessly the next generation of leaders takes on this responsibility will depend greatly on how well their development is supported.

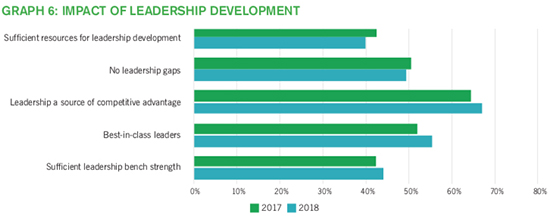

In order to do this, we need a measure of leadership development impact. Everyone has a somewhat different perspective on what constitutes success; therefore, we reviewed the literature and identified five outcomes most experts agree provide a good indication of leadership development performance.

- Leadership is a source of competitive advantage: Do senior executives acknowledge the importance of leadership development to the organization’s success?

- Best-in-class leaders: Are other companies trying to recruit their leaders away?

- No leadership gaps: Does the organization have significant gaps in leadership capacity?

- Sufficient resources: Do organizations have the necessary resources to effectively develop their leaders?

- Sufficient leadership bench strength: How satisfied is the company with its ability to replace departing leaders?

Graph 6 shows the percentage of companies that indicated effective performance on these outcome measures in both 2017 and 2018. The vast majority of respondents in both years agrees that top management acknowledges leadership is a source of advantage (67 percent), and a small majority agrees it has best-in-class leaders (55 percent). However, for the other outcome indicators, the majority is not so optimistic. Results went down from last year on the critical issues of having sufficient resources and closing leadership gaps.

This combination of insufficient resources and increasing leadership gaps is a dangerous one. With the retirement of the Baby Boom generation, this gap in leadership capability will only grow, and if there are limited resources to prepare the next generation of leaders now, many organizations will be ill prepared for the future.

To determine the actions that more effective organizations are taking to successfully develop the next generation of leaders, we combined (averaged) these five measures into an overall score of leadership development performance. We then divided averages into three groups based upon the scores.

- High Performer: Organizations that received the highest scores across these five items, indicating they are achieving the highest level of leadership development outcomes

- Moderate Performer: Organizations that received scores in the middle range, indicating they are partly achieving their desired leadership development outcomes but have not achieved full success

- Low Performer: Organizations that received the lowest scores, indicating their leadership development efforts have not achieved much value

By categorizing organizations in this way, we can ask the key question: What are high-performing leadership development organizations doing that low- or moderate-performing organizations are not? In other words, what are some of the actions you can take to improve your leadership development outcomes?

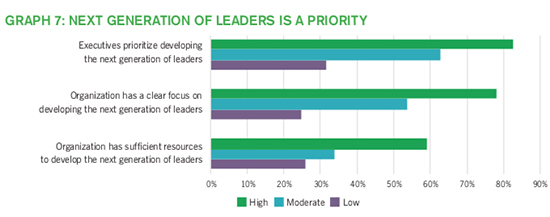

HIGH PRIORITY

One potential cause of greater effectiveness is that higher- performing organizations make developing the next generation of leaders a priority. As Graph 7 shows, high-performing organizations are significantly more likely to indicate that executives prioritize the development of the next generation, the organization has a clear focus on the next generation, and sufficient resources are directed toward developing the next generation of leaders.

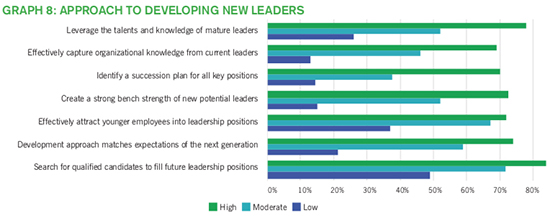

DEVELOPMENT APPROACH

High-performing organizations approach leadership development differently than lower-performing organizations. Graph 8 shows that high-performing organizations are more likely to leverage the knowledge of mature leaders, take steps to capture organizational knowledge, have a succession plan, maintain stronger bench strength, actively seek to attract younger leaders with leadership potential, and tailor their leadership development approach to younger learners.

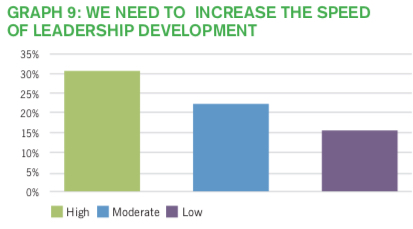

NEED FOR DEVELOPMENT SPEED

A clear difference between high-, moderate-, and low-performing organizations is the perceived need to increase the speed of development. As shown in Graph 9, low-performing organizations perceive a greater need to increase the speed of development, with more than 30 percent indicating it is a critical need. Only 15 percent of high-performing organizations perceive the same need.

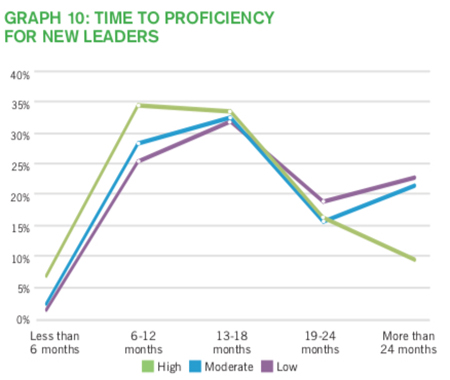

The reason for this is made clear in these organizations’ responses to how long it takes to bring a new leader to a high level of proficiency. As shown in Graph 10, 75 percent of high-performing organizations indicate it takes less than 18 months to bring a new leader to a high level of proficiency, whereas only 58 percent of low-performing organizations share that view. Thus, lower-performing organizations have a longer way to go to have an efficient leadership development process.

TRANSITIONING NEW LEADERS

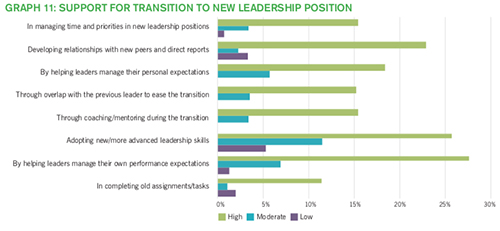

One of the greatest areas of difference between high-, low-, and moderate-performing organizations is the degree to which organizations support new leaders in the transition to a leadership position. As Graph 11 shows, high-performing organizations are much more likely to help new managers through the transition by helping them manage priorities, develop relationships, overlap with the existing manager, and advance their leadership skills.

CROSS-GENERATIONAL SUPPORT

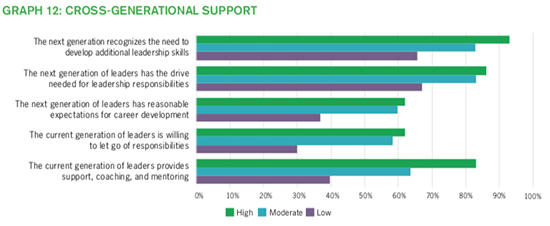

Much has been made of the need for support across the generations for making the transition from one generation of leaders to the next. As is evident in Graph 12, there are meaningful differences between high- and low-performing organizations in the degree of cross-generational support. Most organizations see the next generation as recognizing the need for new leadership skills and being committed and driven to take on these responsibilities. But low-performing organizations see the current generation as much less likely to hand over responsibilities to the next generation or to provide them with coaching. All organizations also feel that many in the next generation may have unreasonable expectations for career development and promotions.

GREATEST DEVELOPMENT BARRIERS

When asked to name their greatest challenge to developing the next generation of leaders, respondents offered a wide range of answers. The most frequent response is a variation of lacking sufficient leadership development resources. For example:

“The speed at which we need to continue to promote and develop new leaders is tremendous. We are ramping up our organization at incredible speed, but developing so many leaders in so little time is challenging.”

Close behind the resource issue is the issue of which developmental model and learning approaches will have the greatest success. Organizations are struggling with leaving behind traditional approaches to developing leaders and adopting approaches more in line with the expectations of younger learners. For example:

“The greatest challenge is the training methodology. The next generation has different expectations and needs. Instructor-led classrooms are not their most popular choice. But developing training on technical platforms—mobile, e-learning, etc.—is not sufficient alone either. We also need active support and participation from high-level leaders to sponsor the programs and current managers to coach and mentor. Learning the skills is not the problem; practice and an understanding of the need for character and competence in leadership development is required—not just creating an app for that.”

A large number of organizations also cite lack of executive support for leadership development, and expectations of rapid advancement from younger leaders as barriers to preparing the next generation.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND LEADERSHIP

The growth of social media has been tremendous. The use of LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media has become common in the workplace. This raises the question of how social media affects leadership.

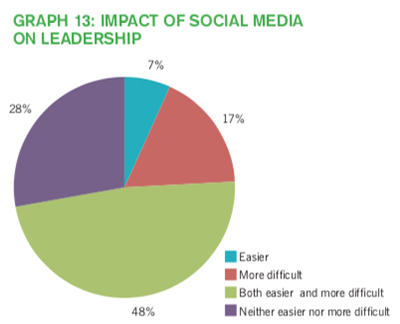

Graph 13 shows the results of the question: Has social media made leading easier or more difficult? The largest group, 48 percent, says it makes leading both easier and more difficult, while 28 percent indicate it has no effect (neither easier nor more difficult). While not surprising, the vast majority, 72 percent, agrees it has a meaningful impact on leadership, for the positive and negative. The results clearly point to a need to understand the role of social media in the organization and in leadership development.

When asked to describe how social media makes leadership easier or more difficult, the responses were overwhelming, with more than 80 percent of survey respondents providing descriptions. This level of participation on an open-ended question is almost unheard of in a survey, indicating that it did, in fact, touch a nerve.

How does social media make leading easier? Responses tended to boil down to two main advantages:

- Greater sharing and interaction among employees and managers. Messaging and discussion boards allow managers to give employees more immediate feedback, share information, and build better relationships despite physical distances.

Social media has made it easier to reach more employees and get feedback faster.

- Greater and easier access to information. Organizations also saw advantages for both employees and leaders in accessing the latest knowledge and information quickly without the effort it once required.

Daily information on certain leadership topics, as well as people talking about their leadership requirements, have helped leaders make quick adjustments to their leadership styles.

Not surprisingly, the ways social media makes leading more difficult parallel the ways it makes it easier:

- Greater sharing can lead to a blurring of personal and business boundaries. People can get too involved in each other’s personal lives. This raises employment law issues, particularly when there are union rules involved.

You know too much about them, and they know too much about you.

- Greater access to information leads to information overload at best and, at worst, confusion when that information is contradictory.

So many items coming at you from every direction cause competing priorities; it is harder to disseminate accurate information from the vast pool of “opinions.”

- Greater sharing also increases the possibility of unintentionally leaking confidential information to others outside the company.

Employees are more likely to post content that is a breach of confidentiality of some kind without realizing the possible impacts and downstream fallout.

STRENGTHENING NEW LEADER DEVELOPMENT

The results of this survey suggest several actions organizations can take to strengthen their leadership development efforts when preparing the next generation of leaders. Specifically, the results indicate you can achieve a greater impact on your organization by:

- Focusing on effectiveness. In the last several years, there has been a focus on efficiency (lowering costs, doing more with less). It is clear from this survey that if the next generation is going to be prepared to take the lead, there must be a shift of focus toward improved effectiveness of the learning. When designing a leadership development process, the first question should be: “Will this improve the leadership behaviors of our people?” It should not be: “How do we make this less expensive or time consuming?”

- Getting executives engaged. Senior executives need to see leadership development as a priority. Encourage the executive team to communicate specific expectations, model desired leadership behavior, create leadership succession plans, and engage direction in leadership development activities.

- Making speed to proficiency a key performance indicator (KPI). There are many reasons you should focus on getting leaders to a high level of proficiency faster. This is not about finding a way to shorten a program from three days to two; it’s about how to shorten the time effective leadership behaviors show up in the workplace from 24 months to 12. One key critical activity is the need to support new leaders in their transition.

- Tailoring learning methods to the younger generations. Organizations have shown great progress in expanding the methods they use in leadership development. Yet despite this, the most frequently used method is still instructor-led classroom training. Newer generations have exposure to a much more diverse and integrated approach to learning than did prior generations, and their expectations are high for how learning can be conducted. A first step is to examine leadership development from a process or journey perspective.

- Engaging all generations of leaders. Organizations that develop programs to prepare the current generation of leaders for the role of coach and mentor have more effective leadership development efforts. Organizations need to encourage the Baby Boom generation to embrace the role of coach and help prepare them to effectively fulfill that role.

- Paying attention to social media and leadership. There is no question the growth of social media is affecting leadership behavior, for the positive and negative. What is not clear is how. More research should be emerging over the next several years; in the meantime, it would be wise to engage leaders in discussions about the potential benefits and risks of social media and track any outcomes you observe.

These best practices of leadership development can help you make a greater strategic contribution to your organization’s leadership. As the next generation of leaders begins leading teams, departments, business units, and organizations, it is your responsibility to make sure they are well prepared for these roles. The very future of your organization may depend on it.

SURVEY METHODOLOGY

More than 500 Learning and Development professionals responded to the 2018 survey. All were employees of companies that create and use leadership development services with their own employees; external providers of learning and development services were excluded from the results.

The survey responses consisted of a well-balanced representation of professionals and decision-makers within the learning and development industry. The majority of respondents (58 percent) had management responsibility, with the largest groups having the title of manager (24 percent) or director (22 percent).

More than half of the respondents (62 percent) were from companies that only operate in the United States; the remaining were composed of global (22 percent) and multinational (16 percent) companies. Organizations were fairly evenly distributed in company size, ranging from less than 100 employees to more than 50,000, with the largest group (22 percent) having 1,000 to 5,000 employees. Individual organizations spent an average of $1.9 million annually on learning and development—46 percent higher than the $1.3 million spent in 2017.

Michael Leimbach, Ph.D., is a globally recognized expert in instructional design and leadership development. As vice president of Global Research and Development for Wilson Learning Worldwide, he has worked with numerous Global 1000 organizations in Australia, England, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States. Over more than 30 years, Dr. Leimbach has developed Wilson Learning’s diagnostic, learning, and performance improvement capabilities. He is editor-in-chief for the ADHR professional journal, and serves on the ISO Technical Committee (TC232) on Quality Standards for Learning Service Providers. Dr. Leimbach has coauthored six books, published more than 100 professional articles, and is a frequent speaker at national and global conferences.

Tom Roth; Bob Lovler, Ph.D.; Nancy Frevert; and Jason Myers of Wilson Learning also made significant contributions to this study.

For more information, contact Wilson Learning at 800.328.7937 or visit WilsonLearning.com.