I recently was asked to lead a commitment ceremony for a couple of dear friends. They had officially married a few months before, but the room in City Hall where the wedding took place was miniscule. Holding a commitment ceremony in a restaurant at a later date enabled many more family and friends to celebrate and show their support for the happy couple.

I had never done anything like this before, so I went to the Internet to seek advice. Luckily, I stumbled across the work of John Gottman, a professor at Washington University, who for years has studied what makes marriages work.

In 1986, Gottman and a colleague, Robert Levenson, set up what journalists called the “Love Lab” into which newlyweds were invited to speak about their relationship—e.g., how they met, a conflict they were facing together, and a positive memory they had. Each couple was hooked up to electrodes (not very conducive to romance); Gottman and Levenson then monitored their physiological responses while they talked—blood flow, heart rates, and how much sweat they produced. Afterward, the couples were sent home, hopefully still speaking to each other.

After a period of six years, the researchers followed up with the participants to see which couples were still married. Two types of marriage relationship were identified from the data: Masters and Disasters.

The Disasters looked calm during the experiment, but their physiological data indicated a state that was far from calm: Their heart rates and blood flow were faster than those of the Masters, and their sweat glands were more active. The more physiologically active couples were, the greater the likelihood the relationship would end in divorce. To the researchers, the Disasters were always in fight or flight mode—always ready to attack or be attacked.

The Masters in the experiment demonstrated low physiological arousal. They were calm and felt connected, which resulted in warm and affectionate behaviors (even when they were in conflict). In short, the Masters had created a climate of trust and intimacy that made them very comfortable with each other.

To dig deeper, in 1996, Gottman created a lab on the university campus designed to look like an attractive bed and breakfast. One hundred and thirty couples were invited to spend a day in the B&B being observed while they cooked, cleaned, listened to music, had a meal, chatted, and just relaxed.

What Gottman noticed was that throughout the day the couples would make “requests for connection,” or what Gottman called “bids.” If, for example, a husband was interested in art and said to his wife, “This is beautiful, come and take a look,” he is not just asking her to look, he is looking for a meaningful, emotional response—a connection. She has the choice to “turn toward” his bid by engaging with him or to “turn away” by ignoring him or responding in a dismissive, sarcastic way (“Sure, real nice.”). She also could respond more aggressively by saying something such as, “Oh, leave me alone. I’ve had a hard day.” By turning toward his bid in an engaging, connective way (“Let me see. Oh, yes!), she would acknowledge what was important to her husband and give it respect.

Our days are full of these bidding interactions at work, too, and how we respond is a critical factor in creating a climate of trust.

When Gottman followed up with couples who had separated after six years, he found that the Disasters only turned toward each other’s bids 33 percent of the time. Couples who were still together after six years turned toward each other’s bids 87 percent of the time.

Reading Gottman’s work, I not only thought of my marriage (40 years and counting), but of work relationships. These relationships—except in “extraordinary” circumstances—won’t have the same level of intimacy as in a marriage, but they are still subject to the turning-toward and turning-away dynamic.

When looking at how the Disasters communicated, Gottman and his colleagues identified what they called The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—indicators that a relationship is likely to fail. Gottman says he can predict 94 percent of the time if a marriage will succeed or not after observing the partners having a three-minute conversation.

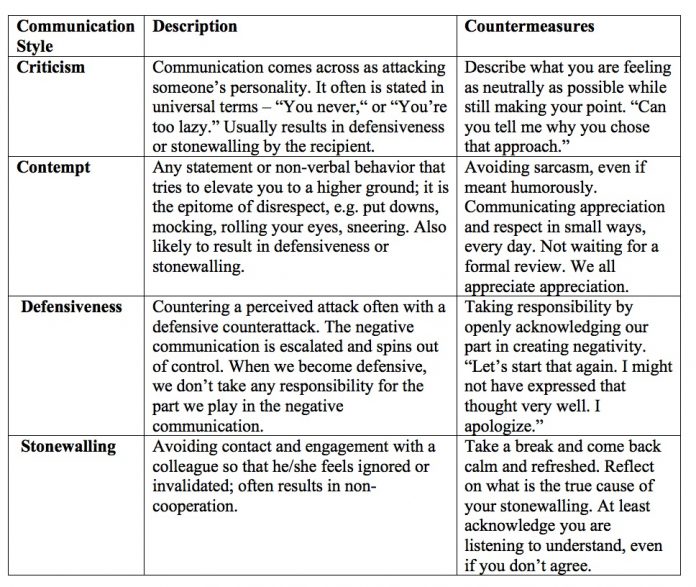

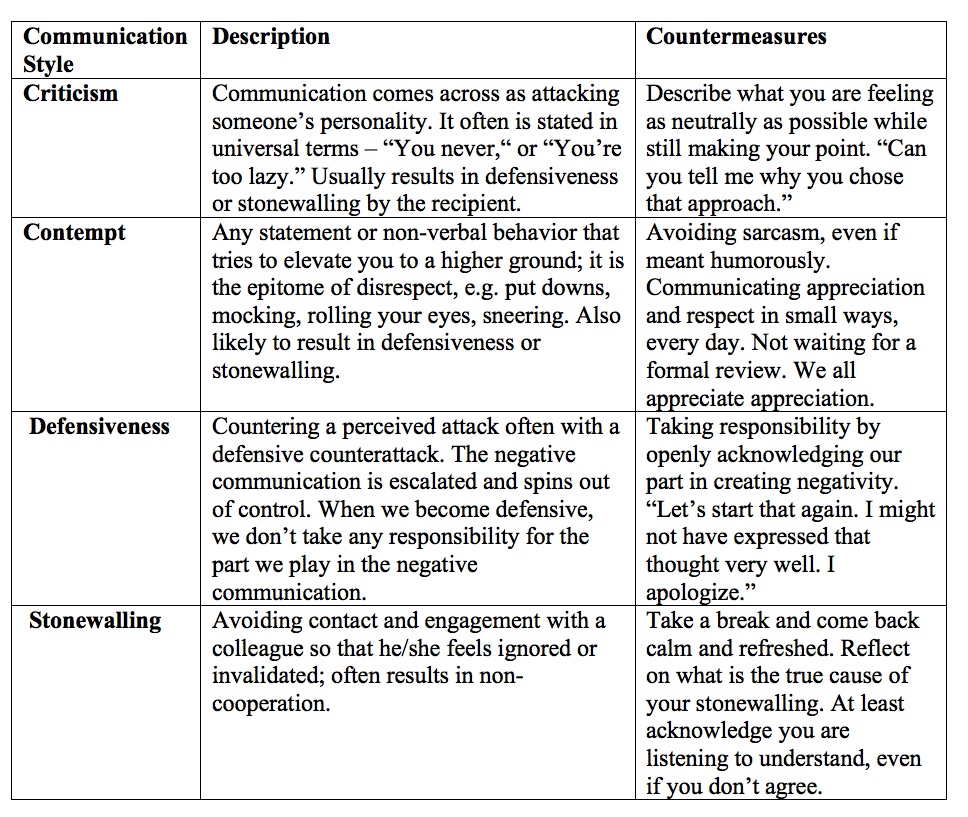

Think about whether you demonstrate any of these Four Horseman of the Apocalypse communication styles at work and what you could do to countermeasure them:

We must never underestimate the destructive power of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse—at home or at work.

Terence Brake is the director of Learning & Innovation, TMA World (http://www.tmaworld.com/training-solutions/), which provides blended learning solutions for developing talent with borderless working capabilities. Brake specializes in the globalization process and organizational design, cross-cultural management, global leadership, transnational teamwork, and the borderless workplace. He has designed, developed, and delivered training programmes for numerous Fortune 500 clients in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Brake is the author of six books on international management, including “Where in the World Is My Team?” (Wiley, 2009) and e-book “The Borderless Workplace.”